The First American Raids Against Sandy Hook

by Michael Adelberg

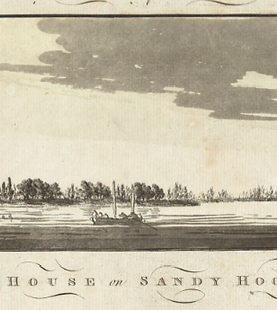

In 1778, Sandy Hook was cut off from the mainland by a channel called “the Gut.” A British guardship protected the lighthouse at its tip. Captain John Burrowes launched the first raid against it.

- December 1778 -

By late 1778, Sandy Hook had been occupied by the British navy for two and a half years. During that time, the British fought off at least three land-based attacks (April 1776, June 1776, and March 1777). They also fortified the Hook and supported Loyalist refugees in establishing a makeshift settlement called Refugeetown. Sandy Hook became the base of operations for Loyalist middlemen, called “London Traders,” who powered the illegal trade between Monmouth County’s disaffected farmers and the British commissary at the lighthouse. Finally, Sandy Hook was the staging ground for raids, great and small, against the shores and villages of Monmouth County.

In 1778, bold privateers such as Yelverton Taylor on the Atlantic shore and William Marriner in the Raritan Bay proved that small American vessels could sting the British and escape without harm if the action was quick. Given this, it was inevitable that local Whigs (supporters of the Revolution) would seek to strike at Sandy Hook. Captain John Burrowes of Middletown Point was the first Revolutionary to surprise attack the Hook.

The Service of John Burrowes, Jr.

John Burrowes, Jr., was a captain in the Continental Army. His father, John Burrowes, Sr., was the Chair of the Monmouth County Committee immediately prior to independence. Burrowes, Sr., was captured by Loyalist raiders in May 1778. Captain Burrowes led the most active and largest company in David Forman’s Additional Regiment which was created to defend Monmouth County. But Forman was stripped of command and the regiment, including Burrowes, Jr., was pulled out of Monmouth County and merged into the main Continental Army two months prior to his father’s capture.

After the Battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778), Captain Burrowes was allowed to stay home for long stretches in order to observe and report on British movements in the Raritan Bay and at Sandy Hook. But Captain Burrowes likely wanted revenge on the Sandy Hook-based Loyalists who took his father and razed his village. He was also an active patriot who understood that the weakened British naval presence at Sandy Hook, whittled down to a single guard ship and company of Loyalist soldiers, made the Hook vulnerable to attack.

The First Raid Against Sandy Hook

On December 18, 1778, Burrowes wrote his commanding general, Lord Stirling (William Alexander) about "a little excursion made on the night of the 15th inst.” He reported that “my cruise was not so favorable as expected,” but it was still quite favorable:

In the evening at 7 o'clock, I set out from this place in three small boats which carried eighteen men, proceeded to Spermacity Cove [on the bayside of Sandy Hook], where I found the sloops I had taken view of the day before; the one that appeared the largest I boarded with six men, the other boats I sent men to board the other two [sloops]. The one I boarded was a tender belonging to the Light House, she mounted 8 swivels, 2 musketoons & 2 blunderbusses. I immediately secured the prisoners & got her away, as also the others; but unfortunately run her ashore and found I could do no more with her. I left her after taking out the prisoners and proceeded to secure the others, which I did. I took fourteen prisoners and some plunder.

The Pennsylvania Packet reported on the event: "Some Jerseymen went in rowboats to Sandy Hook and took four sloops, one of which was armed. They burned three, took one; also taken, nineteen prisoners. The share of prize money per man was £400." An article in the Pennsylvania Evening Post reported the same event, but with slightly different details:

Some row boats about a fort night ago went from Jersey to Sandy Hook where in the night they boarded four sloops, one of which was armed. In carrying them to a place of safety, three of them, by the unskillfulness of the pilots, ran ashore and were burnt. The other, with nineteen prisoners, got safe to New Jersey.

In February 1779, a second raid against Sandy Hook succeeded in taking three additional small sloops. On February 10, the New Jersey Gazette reported "that on Monday night, three prizes taken near Sandy Hook were brought into the Raritan River, one of which had a valuable cargo on board." A second brief reported similarly: "three prizes taken near Sandy Hook were brought into Raritan River, one of which had a valuable cargo on board." It is unknown who led this second raid, but the raiders may have included William Marriner or some of his men given that the captured boats were brought into the Raritan River.

The vessels taken in both actions, with the exception of the one tender discussed in Burrowes’ letter, were not military vessels. They were likely small sloops owned by Loyalist refugees who were facilitating illegal trading between Monmouth County and the British. Regardless of whether these were military vessels or not, interrupting this illegal trade was a valid military objective. The vessels were subject to seizure and could be condemned in the New Jersey Admiralty Courts as valid prizes.

British Weakness at Sandy Hook

The British did not beef up the defenses at Sandy Hook as result of these first two raids. In March 1779, the sloop, Hunter, arrived from Halifax and was left at Sandy Hook as the guardship.

According to documents in the Papers of the Continental Congress, the Hunter suffered desertions throughout 1779 and was well under its full complement of guns. A June document states: “She has lain there as a guard ship last March when she arrived from Halifax, has only six guns mounted, having thrown four overboard in her passage." This is a remarkable contrast to the 40-gun frigates that guarded the Hook in 1776 and 1777.

The weakness of the British defense prompted further insults. On April 10, the Loyalist New York Gazette reported a strange incident that occurred at Sandy Hook on April 2. A Loyalist privateer was sabotaged by a spy named “Smith.” The privateer’s captain discovered "two holes newly bored with an auger and stuffed with fresh cork and some canvas" in the hull of his vessel. The ship nearly sank outside of Sandy Hook, but listed back into sheltered waters where the captain discovered the sabotage on inspection.

A party of Monmouth militia also took a Loyalist vessel near Sandy Hook that spring. Wilson Hunt of Upper Freehold recalled in his postwar veterans’ pension application:

We spied a sloop of war under sail, it appeared as tho' it would land where we immediately hid ourselves in ambush but she did not land. She tacked about and sailed near the British fleet and cast anchor. We marked her position, in course of the evening, we procured a vessel and after dark sailed to the aforesaid sloop, seized her and boarded her immediately and found only the captain and mate on board. The captain surrendered to us at discretion but the mate threatened to alarm the British fleet which lay close at hand, but there was a file of men with fixed bayonets quickly around him - if he opened his mouth they would quickly run him through, upon which he made no further resistance, and we hoisted anchor and bore away for the mouth of the Shrewsbury River which we fortunately struck and ascended our way up river, the next day we were hailed by two men and asked if we did want to buy provisions, having the British colors hoisted they took us to be British, we decoyed them on board and made them prisoners. They were both Tories. We carried the above sloop up to Shrewsbury Town and anchored as near the town as we could get her, where she was declared a lawful prize.

On land, the Monmouth militia and state troops also grew bolder. Cornelius Smock, the son of Lt. Col. John Smock and nephew of Captain Barnes Smock of the Middletown militia, recorded an attack against a Loyalist party on Sandy Hook in 1779:

He was one of thirteen men, with Capt. Barnes Smock, commanded by his father, Lt. Col. John Smock, that went to a place called the Gut on the sea shore near Sandy Hook, and after a smart skirmish, took 26 prisoners - refugees commanded by Lt William Stevens, who was amongst the prisoners - these prisoners were afterwards exchanged for American prisoners then in prison in New York.

Smock further reported that “he was with a party that marched on Sandy Hook and retook John Stillwell's cattle, and brought them off.” Another Middletown militiaman, Chrineyonce Schenck, recalled the same skirmish near Sandy Hook "when twenty-eight or thirty Tories were taken prisoner, together with Captain William Stevens.” The Loyalist publisher, Hugh Gaine, reported in his journal, "an attack upon the Light House at the Hook, but the enemy soon retired."

These early attacks on Sandy Hook set the stage for even more impressive attacks later in the war. Most notably, in January 1780, Major Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee made a bold descent on Sandy Hook during a snowstorm, and throughout 1781 and 1782, the New Brunswick privateer, Adam Hyler, made several successful attacks on British assets on Sandy Hook. These are subjects of later articles.

Related Historic Site: Sandy Hook Lighthouse

Sources: John Burrowes to Lord Stirling, New York Historical Society, MSS John Burrowes; Edwin Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties (Bayonne, NJ: E. Gardner and Sons, 1890) p 194-202; Edwin Salter, Old Tims in Old Monmouth (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1970) p 127-8; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, p 41; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, p 58; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; National Archives, Papers of the Continental Congress, reel 187, item 169, #35, 116, 136, 191; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Wilson Hunt of KY, www.fold3.com/image/#24273269; National Archives, Revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Cornelius Smock; Allan McLane, Army and Navy Chronicle (New York: Benjamin Homans, 1838) p 130-1; Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Journals of Hugh Gaine, Volume I (New York: Dodd, Mead 81 Company, 1902), vol. 2, pp. 87; Paul Leicester Ford, ed., The Journals of Hugh Gaine, Volume I (New York: Dodd, Mead 81 Company, 1902), vol. 2, pp. 87. Providence Gazette, August 25, 1781; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Chrineyonce Schenck.