Admiralty Courts Held at Barton's Tavern in Allentown

by Michael Adelberg

In April 1776, the Continental Congress authorized privateers to capture British ships. The legality of 58 ship captures were judged at Admiralty Courts held at Gilbert Barton’s tavern in Allentown.

- July 1778 -

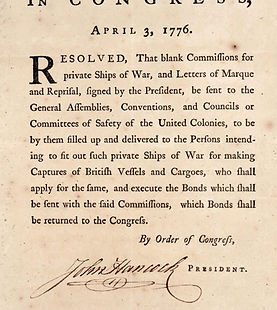

With the entry of France into the war, the British navy re-assigned ships away from the Atlantic Seaboard to protect other parts of its sprawling empire. The British now had less ability to protect ships coming in and out of New York. Privateering, by which American ship captains captured British and Loyalist ships with the blessing of the Continental and state governments, officially started in April 1776, when the Continental Congress sent states “blank commissions for private ships of war… for making capture of British vessels and cargoes.” But privateering along the New Jersey shore did not blossom until spring 1778, when the British naval presence weakened and bold Whigs (supporters of the Revolution) such as William Marriner—demonstrated that British defenses in Brooklyn were permeable.

The capture of a ship was often a simpler matter than determining who had rights to the captured vessel and its cargo. Cases like that of the Betsy, captured after beaching on the Monmouth shore in November 1776, illustrate the months of dysfunction that could follow the capture of a ship. The state of New Jersey established an Admiralty Court address this problem. Admiralty courts heard competing claims on captured vessels, declared a rightful owner, ordered sales, and collected fees for the state.

Historian Donald Shomette dates the establishment of the New Jersey Admiralty Court to an October 1776 law that empowered the Governor to call an admiralty court. It appears that the first adjudicated prize vessel was in early 1777. Richard Somers, commanding the militia at Great Egg Harbor, took the brigantine Defiance. The state lacked a regular admiralty court, but it appears that one was convened and it condemned the prize to Somers. The vessel was sold on the Tuckahoe River near Great Egg Harbor on March 12. Regular admiralty courts did not convene with public announcements, advertising that all claimants on the vessel could come forward, until fall 1778.

Starting in 1778, and continuing into 1783, the State of New Jersey convened dozens of admiralty courts. While most prize vessels taken by privateers were brought into port at Little Egg Harbor or Toms River, the state chose to hold its admiralty courts well inland—perhaps because holding courts on the shore might prompt a British/Loyalist attack or spark riots from locals with a vested interest in the court’s decision.

Allentown as Top Site for Admiralty Courts

The majority New Jersey admiralty courts met at the tavern of Gilbert Barton in Allentown. The selection of Allentown as the host site for the majority courts was not accidental. Allentown was thirty miles inland and was connected to Egg Harbor and Toms River via roads. It was also close to Burlington, Princeton, and Trenton, seats of the New Jersey government. After June 26, 1778, when the British Army left Allentown on its march across New Jersey (leading to the Battle of Monmouth two days later), Allentown was safe from British/Loyalist attacks.

Barton owned the village’s leading tavern. His loyalty to the Revolution was well-understood; he testified against Loyalist insurrectionaries before the New Jersey Council of Safety in 1777 and was the father of a Continental Army captain, William Barton. His tavern hosted Upper Freehold Township’s annual town meeting. Barton sold and leased livestock to the Continental Army even when it probably was not to his economic advantage. He was also a brother-in-law of Charles Petit of Egg Harbor, the shore’s most influential political leader and a man heavily invested in the flourishing privateer industry at Little Egg Harbor and the village of Chestnut Neck, just upriver from the harbor.

The first New Jersey Admiralty Court was advertised in the New Jersey Gazette on June 6, 1778, but was not held until July 13. The long lag probably is attributable to the march of the British Army across New Jersey in late June. When it did convene, the court adjudicated:

the captured sloop, Duck, claimed by Joseph Wade;

the sloop, Hazard, claimed by Peter Anderson;

the sloop, Sally, claimed by the "Abraham Boys";

the sloop, Dispatch, and the brigantine, Industry, claimed by Timothy Shaler;

the sloop, Palm, the brigantine, Speedwell, the brigantine, Carolina Packet, and the brigantine, Prince Frederick, all claimed by John Brooks; and

an unnamed schooner claimed by John Potts (of Monmouth County).

It is noteworthy that the majority of the claimants were Pennsylvanians or New Englanders—a trend that would continue at future admiralty courts.

In total, 60 trials adjudicating 58 prize vessels (two re-trials) were held at Barton’s tavern—far more than any other New Jersey Admiralty Court host site. 43 of these cases were held at Barton’s tavern in 1778 and 1779, after which other sites were used more frequently. (See table 7 for the list of vessels tried at Barton’s tavern.) The other sites to host multiple admiralty courts were: The Burlington County Courthouse, Rensselaer Williams’ House at Trenton, and Isaac Wood’s House at Mount Holly. In Upper Freehold Township, admiralty courts later in the war were listed as being hosted at the house of Benjamin Lawrence and “Randle’s Tavern.”

Gilbert Barton died in 1782 (his will was dated February 21). Lawrence was his son-in-law and likely moved into Barton’s tavern, even if only temporarily. There is a good chance that Barton’s tavern and Lawrence’s house were the same place. Local historian John Fabiano notes that Barton’s tavern became Randle’s tavern when the Barton family sold it to the Randolph family (Randle was a nickname for Randolph). Adonijah Francis, the owner of Allentown’s other tavern, also hosted one admiralty court. James Green of Colts Neck became an innkeeper at Freehold later in the war and hosted an admiralty court; no other Monmouth County site hosted a court outside of Allentown.

New Jersey Admiralty Court records no longer exist, but the admiralty court announcements printed in the New Jersey Gazette provide important information on what transpired in these courts. Through these announcements, we know the men who claimed the prize vessel, the men who were alleged to have lost or forfeited the vessel, and the type of vessel. John Burrowes, Jr., of Middletown Point, who served as captain in the Continental Army into 1779 (starting in David Forman’s Additional Regiment and later serving in the New Jersey Line), became the Admiralty Court’s Marshal in 1780 and announcements carry his name after his appointment. He served as Monmouth County’s sheriff concurrently for two years.

At least eleven Monmouth County militia officers took prizes during the war. All of these Monmouth County claimants, except Asher Holmes of Marlboro, lived near the shore. At least three of the captured vessels (probably more) had grounded on shore. The vessels taken by Monmouth Countians were a combination of captures at sea and vessels that grounded on the shore. Interestingly, two Monmouth County Loyalists operating ships out of Staten Island—Richard Reading and Thomas Crowell—lost vessels that were condemned at admiralty courts in Barton’s tavern.

The most prolific privateer captains were from New England or Philadelphia. For example, Samuel Ingersoll of Salem, Massachusetts had four prizes condemned to him at Barton’s tavern and Yelverton Taylor of Philadelphia had three prizes condemned there. Raritan Bay’s most prolific privateer, Adam Hyler of New Brunswick, also had three prizes condemned to him at Barton’s tavern. These men were heroes in their day and a prize being condemned to a privateer was a cause for celebration. It is easy to imagine significant bar tabs being run up at Barton’s tavern on the nights when prizes were condemned. Hosting admiralty courts was, no doubt, good for business.

Shortcomings of the Admiralty Courts

Admiralty Courts did not end all controversies about claims on captured vessels. A 1780 Dover and Stafford townships petition to the New Jersey Assembly complained:

A number of vessels have lately been stationed along the shores… and that there is no law of this State, as they allege, clearing ascertaining what proportions of said vessels or cargoes shall belong to captors of preservers, which has given occasion to many suits.

Some prizes were indeed the subject of litigation and counterclaims long after the New Jersey admiralty courts finished their work. This was commonly because the provenance of the vessel was not known when the New Jersey admiralty court awarded the prize to the claimant. American vessels taken by British ships and then retaken by American privateers could bog down in long litigation.

At least three of the vessels tried at Barton’s tavern were known to be American vessels taken by the British and then retaken by American claimants. For example, a January 2, 1782, admiralty court announcement noted that William Treen and Joseph Edwards ("of the whaleboat Unity") claimed the sloop Betsy (not the same vessel discussed above) formerly captained by Joseph Burden. The Betsy was originally a New Jersey vessel taken by the British off the Delaware Bay before it was retaken on the New Jersey coast by Treen and Edwards.

One particularly complicated case brought before the Admiralty Court in 1783 involved Colonel David Forman’s seizure of two vessels, Diamond and Dolphin, at Little Egg Harbor. They were owned by the New England privateer Nathan Jackson. Forman had evidence that Jackson was secretly playing both sides, operating as a Yankee privateer when convenient and trading with Loyalists in New York when his cargo could fetch a better prize there. The Admiralty Court awarded the vessels to Forman despite Jackson contesting the claim. The court’s decision was upheld by the New Jersey Supreme Court when Jackson sought redress there. Jackson then sought redress in the Continental Congress’s court to hear interstate disputes, apparently without success. This is the subject of another article.

Curiously, it appears that many vessels taken as prizes on the New Jersey shore were never brought to the Admiralty Court. William Marriner, for example, captured a number of enemy vessels between 1778 and 1780. In May 1780, the Pennsylvania Gazette, advertised the sale of two prizes taken by Marriner near Sandy Hook, Black Snake and Rattle Snake, along with a pilot boat. These were apparently American privateers captured by the British navy, and then re-taken by Marriner.

It does not appear that these prizes were adjudicated in admiralty court (based on court announcements) even though Marriner carried a Letter of Marque (privateer license) from the state. (Note: The Black Snake was purchased by Joseph Randolph of Toms River and re-commissioned as a privateer captained by Joshua Huddy.)

The New Jersey Court of Admiralty passed out of existence when the war ended. The courts certainly did not solve all of the problems associated with assigning a captured ship to a new owner, but it improved upon the vacuum that preceded it. Better documentation would shed greater light on whether most of the court’s proceedings were straightforward assignments of a ship to a single claimant, or contested affairs between individuals with conflicting claims. Whatever its shortcomings, the New Jersey Admiralty Court was a good example of the fledgling government quickly devising \a new institution to meet a need.

Related Historic Site: The Old Mill

Appendix:

Table 7 : Prize Vessels Adjudicated at Barton’s Tavern

Sources: Continental Congress authorizes Letters of Marque, Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/09/massachusetts-privateers-during-the-siege-of-boston/letter-of-marque/ ; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 2, pp. 251-2, 258-9, 272; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 2, pp. 469-70; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, pp. 54, 60; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, p 330; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, pp. 385, 420; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, pp. 481, 486-7; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, pp. 513, 524; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 2, pp. 251-2, 258-9, 272; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 2, pp. 469-70; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 4, p 147; William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 75; Donald Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast (Shiffer: Atglen, PA, 2015); William Nelson, Austin Scott, et al., ed., New Jersey Archives (1901-1917, Newark, Somerville, and Trenton, NJ: 1901-1917) vol. 5, pp. 139-140; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 5, p 170; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 4, p 358-9; Charles Hutchinson, Allentown, N.J. its Rise and Progress (Part 15), Allentown Historical Society; Petition summarized in: The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, March 13, 1780, p 157; Correspondence from John Fabiano; Huddy’s privateer commission is in Catalog of the Exhibition: Joshua Huddy and the American Revolution, Monmouth County Library Headquarters, October 2004.