Colonel Tye and the Black Brigade

by Michael Adelberg

The British promised freedom to slaves who would run away and come behind British lines. One of these men, Tye, led a group of former slaves on a string of raids into Monmouth County in 1780.

- June 1780 -

Even before the Declaration of Independence, British leaders sought to use America’s large African-American population as Loyalist soldiers. In 1775, Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s Royal Governor, promised freedom to the slaves of rebels who would join his Ethiopian Brigade. When Dunmore was chased out of Virginia, he brought these men with him. They boarded a ship bound for Sandy Hook and relocated to New York shortly after the British Army’s landing in America.

As noted in prior articles, Monmouth County’s large African-American population was restive at the start of the Revolutionary War. Whether enslaved or free-but-poor, nearly all African Americans in the county were agricultural laborers. While the county’s Quakers were committed to the manumission of slaves, they only impacted a fraction of African Americans in the county. Shortly after the British Army landed at Sandy Hook on June 30, 1776, runaway slaves sought their freedom with the British.

Individual African American Loyalists in the Local War

African Americans were not permitted in the New Jersey Volunteers (the British Army corps for white New Jersey Loyalists) but they were active in the local war around Monmouth County. Individual African Americans participated in the December 1776 Loyalist uprisings. In early 1777, shortly after Whigs (supporters of the Revolution) regained control of Monmouth County, a slave named Sip warned about a posse coming after him. According to a deposition:

The said Negro [Sip] supposed that the damn Rebels would soon be after him, but if they did, he would take shot amongst them; Sip at this time had a gun with him, that he got from Peter Wardell, a Refugee Tory.

Also in 1777, two slaves were arrested for “having been in arms and aiding the Enemy” and two other slaves, Joe and Scipio, were arrested by Captain John Dennis of Shrewsbury “on suspicion of intending to join the enemy.” They were released back to their masters after spending five months in jail.

African Americans were soon serving as sailors on Loyalist ships on the Jersey shore. In September 1778, the Continental Army’s Commissary of Prisoners, Thomas Bradford, noted that privateers at Little Egg Harbor had taken Black men prisoner. He asked Congress if "Negroes or mulattoes taken at sea by the States should be liberated or held for exchange, or in what manner they should be disposed of?" A year later, the New Jersey Admiralty Court advertised a court in Burlington where the Philadelphia privateer, Samuel Ingersoll, would have "the following Negro slaves lately captured by him, to wit Edward McCuffee, William Bristol, John Coleman, Joseph, Cato and Richard" condemned to him as prizes of war.

There are scattered mentions of individual “Negroes” and “Blacks” participating in Loyalist raiding parties from 1778 into 1780. As larger Loyalist raiding parties under military officers gave way to smaller, irregular parties that practiced “man-stealing,” the prominence of African-Americans increased. The Loyalist Royal Gazette reported that on June 6, 1779, “an inhabitant of said County was taken off by four Negroes." Then, on July 20, the Loyalist New York Gazette reported that:

About fifty Negroes and refugees landed at Shrewsbury and plundered the inhabitants of about eighty head of horned cattle, about twenty horses and a quantity of wearing apparel and household furniture. They also took off William Brinley and Elihu Cook, two of the inhabitants.

A few months after that, Samuel Lippincott was kidnapped out of his bed by a small party of African Americans. Another small party of African-Americans stole horses and then skirmished with militia at Little Silver, as recalled by Samuel Johnson:

That in the night, one John Newman, a sentry, was fired upon and his pocket was shot through by some of the refugees. The next morning, about sunrise, a colored man, a Negro by the name of Moses, with his gun on his shoulder, was approaching the house where the company was stationed. When he perceived the militia, he immediately turned about & went down the field, upon which the deponent and others followed him, he then turned short and made for a creek called Little Silver of about 200 yards wide. He went in the creek, and the light horse under Captain Walton [John Walton] followed him, as did this deponent and the rest of the company all of whom followed at him whilst in the water, and just at the time he was making the land on the other side of the creek, a rifleman by the name of Alexander Erlich [Alexander Eastlick] fired and wounded said Negro.

In the actions above, African Americans operated under white officers or in small parties.

However, in early June 1780, a “company” of “fierce” African-Americans battled militia at the Battle of Conkaskunk. This is the first mention of a large unit of African Americans acting together. It was also the first mention of their very effective leader, Tye. The men would be known as the “Black Brigade” and Tye would be known as their “Colonel”. (Most historians presume that Tye was the former slave, Titus, who freed himself from John Corlies of Shrewsbury in 1775. Some argue that Tye went to Virginia in 1775 to join Dunmore’s African American brigade.)

The Raids of Colonel Tye and the Black Brigade

We know little about the men who served in the Black Brigade. The author’s prior research and the research of Graham Hodges shows that several dozen Monmouth County slaves escaped slavery during the Revolutionary War, but only a few can be traced to the Black Brigade. There are no British documents that discuss the formation of the Black Brigade, but we know that it was not part of the British Army because it is not listed in any British muster rolls or pay records. It can be presumed that the Black Brigade lived off the sale of goods taken during their raids.

By 1780, at least in the warm months, Sandy Hook had a settlement known as Refugeetown—populated by London Traders and partisans who raided for a living. There are just a few fleeting descriptions of Refugeetown. In 1777, when the Loyalist camp was likely only a few huts, Ambrose Serle, a British officer, called it “a dismal, barren spot.” In 1780, Colonel David Forman estimated that “in the cedars are about 60 or 70 refugees, white and black." By 1781, Refugeetown, which was raided by the bold privateer, Adam Hyler, included a fortification described as “a small fort, in which twelve swivel guns were mounted.” Refugeetown was also described a place “where the horse thieves resort.” But Refugeetown was no resort—it lacked fresh water and soil for crops. It is doubtful that men stayed there any longer than necessary.

From Refugeetown, Tye (carrying the honorific title of “Colonel”) carried out a string of raids into Monmouth County. The first Tye-attributed raid occurred in June 9, reported in the New Jersey Gazette:

Ty, with a party of about twenty blacks and whites, last Friday took and carried off prisoners, Capt. Barnes Smock and Gilbert Van Mater; at the same time, spiked up the iron four pounder at Capt. Smock's house, but took no ammunition; two of the artillery horses, and two of Capt. Smock's horses were likely taken off. The above Ty is a negro who bears the title Colonel and commands a motley crew at Sandy Hook.

Philadelphia newspapers carried the same article. A Loyalist New York newspaper reported: "The noted Col. Tye with his motley company of about twenty blacks and whites, carried off as prisoners Capt. Barney Smock and Gilbert Van Mater, spiked an iron cannon and took four horses. Their rendezvous was at Sandy Hook." The raid was discussed by David Forman in a letter to Governor William Livingston:

A party of Negroes about thirty in number did this afternoon attack and take Captain Barnes Smock and a small party that were collected at his house for their mutual defence. This was done with the sun one hour high, 12 miles from one of the landings and 15 miles from the other.

Tye’s next raid occurred on June 21, printed in the New Jersey Gazette and Pennsylvania Evening Post:

Yesterday morning, a party of the Enemy, consisting of Ty with 30 Blacks, thirty six Queens Rangers and thirty Refugee Tories landed Conkaskunk. They, by some means, got in between our scouts undiscovered and went to Mr. James Mott, Sen., plundered his & several neighbor's houses of almost everything in them and carried off several… We had wounded, a Lieutenant Hendrickson had his arm broken, two privates supposed mortally, and a third slightly, in a skirmish with them on their retreat. The enemy acknowledges the loss of seven men, but we think it much more considerable."

The Black Brigade captured Mott, Jonathan Pearce, James Johnson, Joseph Dorsett, William Blair, James Walling, Jr., John Walling, Sr. (son of Thomas), Philip Walling, James Wall, and Matthew Griggs. Tye also captured: "several Negroes and a great deal of stock; but all of the negroes, one excepted, and the horses, were re-taken by our people.” This raises the possibility that Tye’s men, many of whom were runaway slaves, captured other slaves.

Militiaman, James Wall, recalled being taken in this raid in his postwar pension application: “While at the house of one Joseph Dorsett, together with eight others in the neighborhood, were taken prisoner by a party of Tories & carried to the city of New York & confined there in the Sugar House for six months.” The most prominent man taken that day, Assemblyman James Mott, later prepared "A List of Goods Taken by the Enemy on the 20 or 21st Day of June, 1780.” His losses included:

"a Negro boy about 15 years old" - £100;

Wagon, iron traces, collar & tuck line - £18;

1 bull calf - £3;

4 beds & blankets - £40;

500 lb. of beef - £18 15s;

4 pair of pants, shirts, stockings and jackets - £3 5s;

2 mirrors and books - £1 10s;

Pewter dishes, plates & spoons; lines & ropes; knives & forks; earthen ware and glasses; desk;

"1 barrel of tobacco and sundry other articles";

Several additional items were listed as damaged: 2 desks, case & bottles broken; great cupboard; chest of drawers; boots; shoes and handkerchiefs; house doors, windows and closets. The Black Brigade also took "1 side of leather taken from Joseph Dorsett, three hides burnt at Joseph Dorsett's." The long list of home goods suggests that the Black Brigade was as focused on plunder as any military objective.

The militia fought Tye’s party. A receipt from Dr. Thomas Henderson shows that he treated Walter Hyer for wounds from a cutlass blow to the head, and Garrett Hendrickson lost the use of his right arm from wounds during fighting. A few days later, on June 25, another militiaman, Benjamin Van Cleave (not the farmer of the same name whose grain was seized, sparking a fight between local leaders), recorded another skirmish with the Black Brigade at Shrewsbury, "was in a quite a smart engagement with a band of Refugees headed, or said to be, by a Negro called Colo. Tye.” (Appendix #1 collects mentions of Tye in postwar pension applications that are not pegged to a time or place.)

After this string of raids, Tye was apparently less active. No doubt, selling plunder and dividing up prize money took some time. Tye’s men, with money in their pockets, were likely happy to have some time away from the dangerous work of raiding.

Tye’s next raid was apparently on August 17. A militia document titled “A List of those of Warned on the Alarm of August 17, 1780, to march after Colo. Tye" documents that only two militiamen on the list - Joseph West, Thomas West – responded to the alarm, while fifteen men were delinquent. The document demonstrates that the combination of punishing manstealing raids and Tye’s renown had dispirited the Shrewsbury militia company. The details of Tye’s August 17 raid are unknown.

A Loyalist party, likely led by Tye, raided again on August 22. The New York Gazette reported: "Yesterday were brought into this town a Colonel and Major Smock, of the Monmouth County militia, one of these was of the community of Associated Retaliators upon the Tories." The New Jersey Gazette wrote of the same incident, "Hendrick Smock, Esquire, and Lieut. Col. John Smock of Monmouth County were lately made prisoners by a party of the enemy from Sandy Hook and carried to New York."

Tye would launch one more raid. On August 31, he led his largest party—some 70 men—further inland than any previous raid. He went to the tavern of Captain Joshua Huddy at Colts Neck and took Huddy after a stubborn defense. The Loyalists were engaged by a militia party while loading their barges. Huddy escaped and Tye was fatally wounded in the ensuing skirmish. (This raid is the subject of another article.) The Black Brigade was never again as successful as it was in summer 1780, though African American Loyalists continued to participate in raids well into 1782.

British proclamations of freedom to runaway slaves (see Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation in Appendix #2) were not beneficent. Upon reaching British lines, former slaves had few options. There was a continual need for trench diggers and sailors, but these low wage jobs were likely unattractive to most New Jersey African Americans, who had been farmhands. Idle black men were often kidnapped and forced to become sailors; some were sold back into slavery in the Caribbean. Through the end of the war, African Americans were unwelcome in the Loyalist corps of the British Army, even as the Continental Army integrated. While the British freed slaves, they did little to assist them.

The remainder of the Black Brigade were relocated—with families—to Canada at war’s end.

Remembering Colonel Tye

Eighteen months after Tye’s death, after Associated Loyalists razed Toms River. They recaptured and hanged Captain Huddy. Outraged Whigs used the opportunity to compare Tye favorably to the White Loyalists who led the Toms River raid: "[Tye was] justly to be more feared and respected than any of his brethren of a fairer complexion.” Some antiquarian accounts, perhaps informed by verbal tradition, assert that Tye was more respected by Whigs than white Loyalist leaders.

Some recent documentaries on the Revolutionary War have included content about Tye, as have recent African American history documentaries. A handful of modern historians, including those of Graham Hodges and David Hackett Fisher—have written about Tye. Feats have been attributed to Tye that may have been performed by other Loyalists and “facts” have been attached to Tye that appear unprovable. Fisher noted that the Black Brigade was "allied with British forces, but they were independent fighters for their own freedom." Indeed, the men of the Black Brigade maintained their freedom through raiding—but we lack evidence to suggest that the Black Brigade were “freedom fighters” beyond meeting their own needs.

By any measure, Tye was the most effective of Sandy Hook’s Loyalist irregulars. But the pervasive racism against Tye and other Black men does not change that the Black Brigade were kidnappers and plunderers. Human motivations are complex, but the men of the Black Brigade likely turned to raiding because it offered more autonomy and money than the alternatives. Like others caught in Monmouth County’s vicious local war, Tye and his men did what they needed to keep coins in their pockets during a very difficult period. We lack evidence that service in the Black Brigade was a higher calling.

Related Historical Site: Sandy Hook Lighthouse

Appendix 1: Other Mentions of Colonel Tye or Black Brigade in Veterans’ Pension Applications

Matthias Handlin

“He was about 15 years of age when he went out in the militia under Captain Benjamin Van Cleave … at the time, the Tories and Negroes landed at Long Branch about 3 or 6 miles below Shrewsbury... they had a battle with them, he well recollects that they killed Mr. Talman's negro, who appeared to be the commander of the Negroes."

Samuel Herbert

“Was in a skirmish with a company of refugees said to have been commanded by a Negro called Col Tye -again was out as a substitute for one Samuel Hendrickson.”

William Lloyd

“At one time the Negro refugees fired upon a sentinel and pursued them to a place called Jumping Point on the Shrewsbury. We went into the river with one of the men, he got tired a distance from land and could swim no further. I swam to him... and saved his life.”

William McBride

"Marched down to Cedar Bridge in search of Colonel Tye, who had a party of Negroes and runaways under him, and were plundering the inhabitants, remained along the shore until the month expired."

Elisha Shepherd

“Continued guarding the lines… until taken prisoner by the refugees under Col. Tye when he was taken to New York and put in the provost’s or hangman’s jail… and continued confined in said prison to the end of the war.” His brother, Jacob Shepherd, testifies: “himself and his brother, Elisha, was taken prisoner by the British in the year that Cornwallis was taken, they were kept prisoners for about five months and he thinks they were exchanged in the month of March.”

Jacob Truax

“Jacob Truax's pension application excerpted: ln 1780, "was in skirmish with Coll. Tie near Eatontown, the refugees were commanded by Tie, a black who was killed during that skirmish."

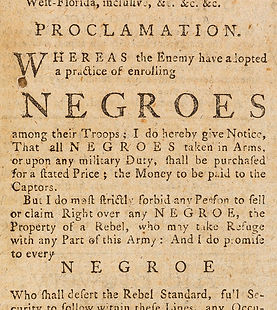

Appendix #2: General Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg Proclamation

By His Excellency Sir Henry Clinton, K. B. General and Commander in Chief of all this Majesty’s Forces, within the Colonies laying on the Atlantic Ocean, from Nova Scotia to West-Florida, inclusive, &c., &c., &c.

PROCLAMATION.

Whereas the enemy have adopted a practice of enrolling Negroes among their Troops; I do hereby give notice, that all Negroes taken in arms, or upon any military duty, shall be purchased for a stated price; the money to be paid to the captors.

But I do most strictly forbid any person to sell or claim Right over any Negroe, the property of a rebel, who may take refuge with any part of this Army; and I do promise to every Negroe who shall desert the Rebel Standard, full security to follow within these Lines; any occupation which he shall think proper.

Given under my Hand at Head-Quarters, Philipsburg, the 30th Day of June, 1779. H. Clinton.

Sources: Michael Adelberg, “’A Motley Crew at Sandy Hook’: Monmouth’s African American Loyalists,” in The American Revolution in Monmouth County (History Press: Charleston, SC, 2011); Thomas Bradford to Congress, National Archives, Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, I78, Misc Letters to Congress, v 3, p 185; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, September 1779, reel 1930; the June 6, 1779 raid is excerpted in William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 403; William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 406; William Nelson, Austin Scott, et al., ed., New Jersey Archives (Newark, Somerville, and Trenton, New Jersey: 1901-1917) vol. 3, p 504; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Samuel Johnson of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/#24646107; John C. Dann, The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980) pp 125-6; David Forman to William Livingston, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, p 423. Francis Pingeon, Blacks in the Revolutionary Era (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1975) p22; Library of Congress, Early American Newspapers, Pennsylvania Evening Post, November 1781; Ambrose Serle, The American journal of Ambrose Serle, secretary to Lord Howe, 1776-1778 (New York: Arno, 1969) p 240; David Forman to George Washington, Monmouth County Historical Association, Diaries Collection, box 2, John Stillwell's Diary (photocopy); Monmouth County Historical Association, J. Amory Haskell Coll., folder 3, Document A; Library of Congress, Early American Newspapers, Pennsylvania Evening Post; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Library of Congress, Early American Newspapers, Pennsylvania Evening Post; New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930, June 28, 1780; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, James Wall of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/# 20365301; List of Goods Taken by the Enemy, Monmouth County Historical Association, Cherry Hall Papers, box 15, folder 11; Walter Hyer and Gerrett Hendrickson’s wounds are discussed in William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 407; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Benjamin Van Cleave; Militia List, New Jersey Historical Society, Holmes Family Papers, box 4, folder 2; New York Royal Gazette excerpted in William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 137; Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application of William McBride of NJ, National Archives, p3-4, 20-2; John Stillwell, Historical and Genealogical Miscellany (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1970) v5, 50-9; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Matthias Handlin of Ohio, www.fold3.com/image/#23563620; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Jacob Truax; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Samuel Herbert of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/#23218962; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Elisha Shepherd of OH, www.fold3.com/image/# 16277477; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, John McBride of Middlesex Co, www.fold3.com/image/#26202858; New York Royal Gazette, July 4, 1779 (see: https://www.philipsemanorhall.com/blog/the-philipsburg-proclamation); Gilje, Paul A. and William Pencak, eds. New York in the Age of the Constitution, 1775— 1800, (Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson Press, 1992), pp. 36, 46 note 63; Graham Hodges, African Americans in Monmouth County during the American Revolution (Lincroft, NJ: Monmouth County Park System, 1990) p 19; David Hackett Fischer, Washington's Crossing (NY: Oxford UP, 2004) p169-70.