Pulaski's Legion and the Osborn Island Massacre

by Michael Adelberg

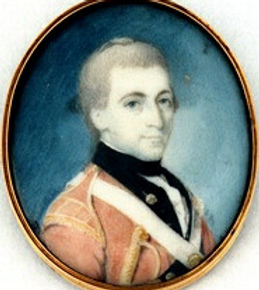

Patrick Ferguson was among the most energetic officers of the Revolutionary War. His attack on Pulaski’s Legion was among the most brutal Revolutionary War incidents to occur in New Jersey.

- October 1778 -

On October 5, 1778, a 1,000-man British-Loyalist raiding party reached Little Egg Harbor (called Egg Harbor at the time), just south of Monmouth County. They blocked the harbor entrance and, with disaffected locals as guides, 300 men in four galleys went upriver to Chestnut Neck, New Jersey’s privateer boomtown. Brief cannon-fire from the boats scattered the local militia from the town. On October 8, the valuable British merchant ship, Venus, and ten other vessels were unloaded and then burned, as were the warehouses and the town’s unarmed fort. Some smaller vessels escaped by upriver, but the success of the attack was near-total.

The raiders returned to the mouth of Mullica River at Egg Harbor. One of their larger ships, Granby, grounded in the harbor and this may be why the raiders stayed in Egg Harbor for the next week. During that time, the raiders sent out parties to destroy nearby salt works (a favorite target of Loyalist raiders) and take unwitting privateers entering the harbor. British leader, Edmund Burke, received a report that the raiders then razed “three salt works, and several stores were destroyed. The Raleigh, a fine American frigate was taken.” The British also sent a party to Cranberry Inlet (the entrance to the shore’s second busiest privateering port of Toms River) to capture another vessel.

Even before the raiders razed Chestnut Neck, American forces were moving to defend the area. Thinking the attack would be made against Elizabethtown, Governor William Livingston mistakenly sent militia from several counties in the opposite direction of the attack. However, George Washington had better intelligence and ordered the new Legion of Kasimir Pulaski (officered by Europeans but manned by Americans) and the artillery regiment of Thomas Proctor to defend Egg Harbor. By October 8, a formidable collection of American forces neared the area: 250 men under Pulaski, 220 men in Proctor's Artillery Regiment with cannon, 50 Philadelphia militia, and 300 Monmouth militia under Samuel Forman. But the American forces were uncoordinated—arriving at different times, from different directions.

Pulaski left Trenton for Egg Harbor on October 6 and, according to the New Jersey Gazette "marched for that place with all his troops in high spirits and with great alacrity." Lacking the strength to attack the British, Pulaski camped ten miles north of their ships, on Osborn Island—a swampy piece of land at the edge of Egg Harbor and the southern tip of present-day Ocean County. Local histories say they stayed in the homes of John Ridgeway and Jeremiah Ridgeway, members of a disaffected Stafford Township family.

Though most of the recruits into Pulaski’s legion were Marylanders and Pennsylvanians, at least one Monmouth Countian enlisted in the Legion as they marched to Osborn Island. Joseph Coward enlisted for eighteen months and probably guided the Legion to its camp, where they arrived no later than October 10. Jonathan Pettit of Egg Harbor would later submit a claim for feeding Pulaski’s men with 40 fowls, 1 barrel of cider, and 2 1/2 yards of new cloth (total value L20 S7) "taken by the men under Genl. Pulaski” on October 10.

By October 14, a stalemate of sorts existed at Egg Harbor. The British raiding force was too strong to be attacked, but Proctor and Philadelphia militia had moved up the Mullica River to defend the state’s interior. To the north, Pulaski and the arriving Monmouth militia blocked further raids into Monmouth County. (The activity of the New Jersey militia is discussed in another article.)

Pulaski’s position was revealed to the British by Carl Joseph Juliat, an officer under Pulaski who deserted to the British. Local teenagers, Thomas Osborn, and Richard Osborn were compelled to serve guides to the British. Well informed about Pulaski’s vulnerable camp, a British-Loyalist party under Captain Patrick Ferguson determined to row ten miles to attack Pulaski’s Legion at night.

The Osborn Island Massacre

The reports of Count Pulaski to the Continental Congress and Captain Ferguson to General Henry Clinton describe what happened on Osborn Island: Pulaski reported having his camp revealed to Captain Ferguson: “One Juliat, an officer lately deserted to the enemy, went off with them… with three men whom he debauched and two others whom they forced with them.” Ferguson reported similarly: “A Captain and six men from Pulaski’s Legion defected to us” and provided information on Pulaski’s camp. Ferguson opted to attack because “the winds detained us” at Egg Harbor.

Pulaski’s description of the attack:

The enemy, no doubt excited by this Juliat, attacked us at three o’clock in the morning with 400 men. They seemed at first to attack our pickets with fury, who lost a few men in retreating. Then the enemy advanced on our infantry. The Lieut. Col. Baron DeBose, who headed these men, fought vigorously, was killed with several bayonet wounds, as well as Lieut. De la Boderie and a small number of soldiers and others were wounded. This slaughter would not have ceased so soon if on the first alarm had I not hastened with my cavalry to support the infantry which then kept up a good countenance; the enemy soon fled in great disorder and left behind a great quantity of arms, accoutrements, hats, blades, etc… We took some prisoners and should have taken many more had it not been for a swamp through which our horses could scarcely walk.

Ferguson’s account of the attack differs on key facts:

At eleven last night 250 men were embarked and, after rowing ten miles, landed at four in the morning within a mile of a defile, which we happily secured, and leaving thirty men for its defence, pushed forward upon the infantry of the Legion, cantoned in three different houses, who are almost entirely cut to pieces. We numbered among their dead about fifty and several officers among whom we learn are a Lieutenant Colonel, a Captain and Adjutant. It being a night attack, little quarter could, of course, be given; so that there are only five prisoners.

Pulaski reported that immediately after the battle, he was unable to “cut off the retreat [desertion] of about 25 men, who retired into the country and the woods.” Given the loss of these men and deaths from the battle, he could not launch a significant counter attack. Pulaski did not report that the arriving Gloucester County militia attacked Ferguson’s raiders during its withdrawal, but was badly defeated. Ferguson also discussed the withdrawal, “The rebels attempted to harass us in our retreat but with great modesty, so that we returned at our leisure, and re-embarked in security.” Ferguson reported his losses at only two dead and two wounded. One Loyalist newspaper claimed that 60 of Pulaski’s men were killed, another stated 53. American newspapers reported Pulaski’s losses “at about 30 men killed or missing.”

Subsequent accounts reveal additional information on the so-called Osborn Island Massacre. Ferguson reported that his men spared the homes of James Willett and the Ridgeways, who hosted Pukaski’s men: “as the houses belonged to inoffensive Quakers, who may have already suffered sufficiently in the night's confusion." But Ferguson was also callous about killing Pulaski’s Legion “which is entirely cut to pieces.” He explained, “It being a night attack, little quarter could be given.”

With accusations building about the brutality of the attack, Ferguson wrote a second account of the attack ten days after his first report:

Capt. Ferguson set off in the night in boats with 250 men, rowed ten miles, landed, marched one mile to a bridge, at which he left fifty men, with the rest he marched a mile farther, surprised and cut to pieces the infantry of Pulaski's legion. Our soldiers were highly irritated against this brutal foreigner, who had given out in public orders to his men, never to give any quarter; in consequence of which our people took only five prisoners, all the rest, were left on the spot, the business being done with the bayonet only. Yet even here Capt. Ferguson had an opportunity of exercising his humanity; the houses in which were the baggage and equipage of Pulaski's legion, belonging to inoffensive Quakers, he left them untouched, rather than distress the innocent inhabitants by burning the quarters.

Ferguson further noted his need to strike quickly given that “the rebel Colonel Proctor being within two miles with a corps of artillery." British political leader, Edmund Burke, reading reports from America, wrote that Pulaski’s sleeping men “were almost entirely put to the sword.” Burke also claimed that “Pulaski had given orders that no quarter should be given to our troops."

Pulaski’s alleged order to grant no quarter seems unlikely since it was Ferguson who launched the pre-dawn surprise attack. Continental Army General William Heath was outraged by Ferguson’s murderous conduct and the weakness of the “no quarter” excuse:

They surprised a part of Pulaski's legion in that neighborhood [Osborn Island], whom they handled very severely. The British pretended that they had heard that Pulaski had instructed his men not to give them quarter; they therefore anticipated retaliation.

A British captain, Charles Steadman, clarified the controversy over Pulaski’s alleged “no quarter” order:

Captain's Ferguson's soldiers were highly irritated by intelligence immediately before received from the deserters [of Pulaski's Legion] that Count Pulaski had given out in public orders to his Legion, no longer to grant quarter to British troops. This intelligence afterwards appeared false; but in the meantime, Captain Ferguson's soldiers acted under the impression that it was true.

Ferguson’s party returned to their ships at 10 a.m. on October 15. The invasion flotilla weighed anchor that afternoon but had to leave behind and burn their flagship, Zebra, which had grounded. They had orders raid along the shore on their back. Ferguson recalled that his men were to "employ ourselves” by “looking into Barnegat and Cranberry Inlets, and destroy and bring off any vessels that may happen to be there, and demolish the saltworks, which are very considerable on the shores of these recesses." Slowed by contrary winds, the British did not return to Sandy Hook until October 22.

Back on Osborn Island, a mob took young Thomas and Richard Osborn, who had guided Ferguson’s men. According to local histories, the mob would have hanged the Osborns but one of Pulaski’s officers saved them by arresting them. Pulaski wrote on October 16, “Two men who guided the enemy were taken in that operation, I have ordered them to Trenton, with some prisoners and arms.” The Osborns were charged with treason and acquitted on October 30 (presumably because they were forced to assist Ferguson).

As for Pulaski, his Legion was decimated and humiliated. They headed north though poor and disaffected neighborhoods where the locals had no love for either European officers or their out-of-state recruits. Pulaski’s difficult march is the subject of the next article.\

Related Historic Site: Little Egg Harbor Friends Meeting House

Sources: Franklin Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor, NJ: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1966) pp 22-4; Wilson, Harold F., The Jersey Shore: A Social and Economic History of the Counties of Atlantic, Cape May, Monmouth and Ocean (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1953) pp. vol. 216-217; John Stillwell, Historical and Genealogical Miscellany (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1970) v3, p477; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Franklin Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor, NJ: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1966) pp 3-5, 29-35; Private Correspondence: Jack Fulmer, Personal Map of Egg Harbor; Damages by Americans, Burlington County Ledger, claim #59, New Jersey State Archives; William MacMahon, South Jersey Towns (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1973) p 302; David Fowler, egregious Villains, Wood Rangers, and London Traders (Ph.D. Dissertation: Rutgers University, 1987) p 192; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Joseph Coward; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Jacob Davidson; National Archives, Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, I42, Petitions to Congress, v 1, p 214; Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; William Livingston to Lord Stirling, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 2, p 457; Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, vol. 12, pp. 981, 984; New York (Royal) Gazette, October 24, 1778; Edmund Burke, An Impartial History of the War in America (R Faulder, London 1780), p 42-3; Patrick Ferguson’s account in Arthur Pierce, Smugglers' Woods, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1960) p 50-1; Franklin Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor, NJ: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1966) pp 124-5; Patrick Ferguson to Henry Clinton, Great Britain, Public Record Office, Colonial Office, CO 5, v93, reel 2, #420-37; Szymanski, Leszek, Casimir Pulaski: A Hero of the American Revolution, (New York: Hippocrene Books, Inc., 1993) pp. 211-2, 214; Richard B Martin, Runaways of Colonial New Jersey (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2007) p307; William Fischer, Biographical Cyclopedia of Ocean County (Philadelphia: A.D. Smith, 1899) p 49; Patrick Ferguson, Report, The Scots Magazine, v43, p 29; Patrick Ferguson to Henry Clinton, Great Britain Public Record Office, CO 5/1089, p 151-3; William Heath, Memoirs of the American War, (Boston: Applewood, 1798), p 208; Franklin Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor, NJ: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1966) pp 132-3; Frederick W. Bogert, "Sir Henry Raids a Hen's Roost,'" New Jersey History, vol. 98, n. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 1980), pp. 228-31; Richard Henry Spencer, "Pulaski's Legion," Maryland Historical Magazine, vol. 13 (1918), pp. 215-24; William Livingston to George Washington, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 3, pp. 80-1.