British Fortify Sandy Hook in Preparation for French Attack

by Michael Adelberg

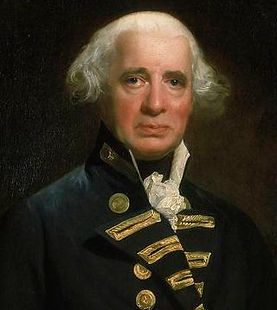

Admiral Richard Howe focused his ships and shore battery into a firing position at the channel above Sandy Hook. Confined to the narrow channel, the French fleet chose not to attack.

- July 1778 -

The Sandy Hook peninsula sits at the entrance of Raritan Bay and Lower New York Harbor. Its lighthouse brings in ships from the Atlantic Ocean. The British navy took the unguarded Hook in April 1776 and held it continuously through the end of 1783—longer than any other piece of the rebelling colonies. The British gradually fortified Sandy Hook following land-based attacks in June 1776 and March 1777. But the threat faced in July 1778—with the arrival of a large French fleet—was on a different scale, and so were the corresponding fortifications.

On July 5, the British Army completed the Monmouth campaign and left for New York via Sandy Hook. This was a few days before the arrival of the French. The German officer, Johann Ewald, described the fortified Sandy Hook Lighthouse as it appeared on that day:

It is built of the most beautiful stones, some thirty feet wide in the square, and is about two hundred feet high. Since the Americans constantly threatened to destroy it, the Light House has been fortified with a stone breast work in which loop holes have been constructed. In the tower itself, port holes for cannon have been cut on all four sides, four of which are on the first floor for defense.

The defenses were built to protect the lighthouse and its one-company guard from land-based attacks. The cannon were likely small and most did not face into the channel where New York-bound ships enter.

Fortifying Sandy Hook

The French fleet anchored off Shrewsbury Inlet on July 11. That same day, British officer Frederick Hamilton noted that construction had begun on a five-gun channel-facing battery. The next day, Major John Andre offered a more complete description of the full scope of efforts underway to fortify Sandy Hook:

The 44th and 15th Regiments were added to these, and Colonel O’Hara [Charles O'Hara] took the command and marched from Bedford to be embarked for Sandy Hook. They were here employed in throwing up a battery of two 8-inch howitzers and three 32-pounders. Eight Companies from the Light Infantry and Grenadiers were distributed on board the ships of war. The Companies were chosen by lot and the whole drew at their own request. The ardor to serve and the confidence in Lord Howe were as conspicuous in the seamen of the transports, who almost to a man were Volunteers to go on board the King’s Ships.

Andre reported seventeen warships arrived at the Hook along with “three sloops, three fire-ships, two bombs and three galleys.” The ships were lined up near the tip of Sandy Hook, so that they could fire on any French ship coming into the channel immediately north of the Hook.

The shore battery still needed cannon. Admiral Richard Howe at Sandy Hook wrote to General Henry Clinton at New York: "I shall be obliged to you to furnish me with a couple of 8-inch Howitzer, with Artillery Men Ammunition &ca., to place on the point of the Hook.” Howe also expressed concern about the lack of engineers and whether Sandy Hook was ready for a French attack:

Your engineer is not yet (that I have heard of) arrived. The wind being easterly, furnishes our adversaries with a favorable opportunity to make their attempt… Some tools will be necessary amongst the other requisites for making a bed & Breast Work for the Howitzer. But a skillfull engineer to direct our undertakings will be a treasure. We wish to borrow a few light infantry of which Duncan [Henry Duncan] writes. No time should be lost in the dispatch of the Howitz &c.

The requested British Army engineer, John Montressor, returned to Sandy Hook on July 13 (he was there a week earlier during the British Army’s withdrawal). He wrote of his activities to complete the channel-facing battery at the tip of the Hook: "I detached 3 engineers to Sandy Hook to construct two batteries for 3 eighteen pounders and 2 howitzers, with tools and materials." More troops continued to arrive; a troop return listed 1,349 men (of which 1,076 “were fit & present”) at Sandy Hook.

In New York, General James Pattison wrote of Loyalists volunteering to man the British ships in this moment of need: "A hot press of seamen began this evening but was soon put to a stop upon a sufficient number of men from the transports turning out as volunteers to serve in the fleet." After the war, David Ramsey, a Continental officer, noted the spirited response from New York City: “The sight of the French fleet raised all the active passions of their adversaries ...the British [and Loyalists] displayed a spirit of zeal and bravery which could not be exceeded.”

Pattison noted that the requested howitzers were on their way: “A battery was begun at the Hook & eighteen pounder were sent down there, also 2 eight inch howitzers." The next day, Pattison noted the loss of a sloop to the French. More ominously, he wrote that "the French were observed to be sounding the channel into Sandy Hook & to take several prizes."

The British placed retired ships next to the shore battery. On July 13, Captain Henry Duncan wrote of the placement of a “fireship” at the tip of Hook, to be set afire and sent toward the French if they entered the channel. Also on site was the aged storeship, Leviathan, which was turned into a 16-gun floating battery. Another navy officer, Peter Alpin, noted 200-New York City volunteers “variously employed" at Sandy Hook. This included rowing casks of fresh water to the men on the dry peninsula. On July 15, Colonel Thomas O’Beirne, noted another asset at the tip of the Hook:

Four galleys were ranged across the narrow part of the channel abreast the Hook; from which situation, in case of attack, they could row upon the shoal and cannonade at such a distance as should be most convenient for the purpose of annoying the enemy.

Sandy Hook as Key British Defenses

On July 15, Colonel Charles O'Hara, the commanding army officer on Sandy Hook, toured the Hook with Admiral Howe. He reported to Henry Clinton on the Hook’s vulnerability: “The French Fleet could cover the descent of troops on almost every part of the coast of the Hook.” O’Hara called for a fort on the south end of Sandy Hook: “So many formidable attempts may be made upon this Island, I conceive that it would be absolutely necessary that a very considerable Reinforcement, not less than fifteen Hundred Men with Six Pieces of Field artillery, would be requisite for its defence.”

O’Hara reminded Clinton of the importance of holding Sandy Hook:

The possession of this post I conceive to be of the greatest importance as it enables Lord Howe under its cover to take a position that puts him upon a Level with the French fleet—who by being obliged to pass the bar by single ships would be beat by our fleet—But were the French masters of this Island, they would by erecting batterys [and] oblige our Ships to quit this present advantageous situation & move higher up the bay—the Enemy would then pass the bar unmolested & attack Lord Howe in line of battle—I must therefore take the Liberty of repeating that I conceive this Post to be of the very first Importance & that an Immediate considerable reinforcement is necessary.

On July 15, O'Beirne underscored O‘Hara’s assessment by sizing up the two fleets: The French held a fourteen-to-nine edge in large warships, though the British had more smaller ships, but some of the British ships remained "wretchedly manned" even with a thousand Loyalist sailor-volunteers ("masters and mates of the merchantmen and traders"). Soldiers were placed on the British ships as marines.

A few days later, Henry Clinton visited Sandy Hook. Montressor wrote that "Sir Henry Clinton went this morning to the Hook." Montressor was also at Sandy Hook and visited the ship-turned-gun platform, Leviathan, which Montressor reported now carried 70 cannon." He noted that "the [French] fleet have now taken eleven sail of our vessels besides the fishing craft." Peter Alpin reported that three French ships approached and the two fleets exchanged long distance fire, "but not the least attention [was] paid to them" because they did not come close.

On July 21, Pattison reported to Admiral Howe about the defenses on Sandy Hook: “All the larger ships of his fleet were ordered to Sandy Hook & the cruisers called in… the fleet was properly arranged & batteries erected on the Hook, where a corps of two battalions was encamp'd.” Pattison observed that because of the narrowness of the Sandy Hook channel, “not more than one or two of their [French] ships at most can come in at a time” during which time the British could concentrate fire on that ship. Knowing this, he concluded, “We have the satisfaction to find that we are pretty secure from an attack in this quarter."

From Sandy Hook, the British observed the French ships moving on July 22. Lord Carlisle, in New York City, speculated that the climactic naval battle would soon begin, “we expect every day to hear of some major event that may be very decisive, as his whole force is collected." A British officer also noted very high tides, "the spring tides were at their highest and that afternoon, thirty feet deep at the bar". So, July 21-22 were ideal days for the large French ships to enter Sandy Hook’s narrow channel.

The French, however, had other ideas. Local pilots had informed them that their largest ships sat too deep in the water to enter the channel. Their fleet, receiving only a fraction of needed provisions from Shrewsbury, decided to sail for Rhode Island—where deeper waters and greater provisions awaited.

With the threat passed, the British quickly divested resources from Sandy Hook. On August 3, Pattison reported that Admiral Howe pulled his fleet away from Sandy Hook, "leaving only the Leviathan, an old 74 gun ship, now carrying 54, and the Amazon of 32 guns." The troops left a week later. Montressor reported on August 10, "The troops evacuated the post at Sandy Hook and proceeded to Long Island, all but 3 companies of Jersey Volunteers."

Had the French arrived a week sooner, the British fleet would have been scattered and unable to resist them, and the British Army could have been cut off in New Jersey. It is quite possible that the American Revolution might have ended on the Navesink Highlands in July 1778. This was not lost on Colonel Thomas O’Beirne who observed, "had the French squadron arrived a few days sooner, or had the evacuation of Philadelphia been deferred a few days later, the whole force of Great Britain on that side of the Atlantic must have been annihilated."

Related Historic Site: Sandy Hook Lighthouse and HMS Surprise (Replica of the Rose) (San Diego, CA)

Sources: Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979) p 138; Frederick Hamilton, The Origin and History of the First or Grenadier Guards (Ulan Press, 2012) vol. 1, p 233; Jack Coggins, Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution, (Harrisburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1969) p 142; Major John Andre, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Naval History Foundation: Washington DC, 2018) vol 13, p 357; Richard Howe to Henry Clinton, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Naval History Foundation: Washington DC, 2018) vol 13, p 359-360; British Army Return, Clements Library, U Michigan, Henry Clinton Papers, July 13, 1778; Gen Richard Howe to Henryt Clinton, Clements Library, U Michigan, Henry Clinton Papers, July 13, 1778; Montresor, John. “Journals of Captain John Montresor.” Edited by G. D. Scull. (New York: Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 1881) p 505-9; James Pattison in Ritchie, Carson I. A., ed., “A New York Diary of the Revolutionary War.” in Narratives of the Revolution in New York (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1975) pp. 242-3; David Ramsey, The History of the American Revolution, Liberty Fund: Indianapolis, 1990, Vol. 2, 88-89; John Knox Laughton, "Journal of Capt. Henry Duncan" in Publications of the Naval Records Society, vol. 20, 1920, p169-70; Clements Library, U Michigan, Peter Alpin Collection, Logbook of the Roebuck; Charles O’Hara to Henry Clinton, Clements Library, U Michigan, Henry Clinton Papers, July 15, 1778; Thomas Lewis O'Beirne, A Candid and Impartial Narrative of the Transactions of the Fleet, Under the Command ofLord Howe (London, 1969), pp. 3 - 15; David Library of the American Revolution, James Pattison Papers, reel 1; Joseph Reed, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed, William B. Reed, ed. (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1847), p 389; Mahan, A. T., The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence, (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1913) pp. 64-8; James Pattison in Ritchie, Carson I. A. “A New York Diary of the Revolutionary War.” in Narratives of the Revolution in New York (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1975) pp. 246; David Syrett, The Royal Navy in American Waters, 1775-1783 (Aldershot, UK: Scolar Press, 1989), p 99; Montresor, John. “Journals of Captain John Montresor.” Edited by G. D. Scull. (New York: Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 1881) p 509.