The Capture of the Venus by Two Privateers and its Aftermath

by Michael Adelberg

The Declaration of Independence forced Americans to take sides. In the month prior to the Declaration, Monmouth Countians authored and signed nine petitions against independence.

- September 1778 -

Privateering along the Jersey shore blossomed in 1778—the appearance of a powerful French fleet in American waters forced British ships into a defensive crouch that extended to waters they formerly ruled. Small and mid-sized privateer ships from Philadelphia and New England started prowling the coastal sea lanes to and from New York harbor and taking British and Loyalist ships with impunity. When British ships were wounded by severe storms or grounded on the Jersey shore, local militia took to their boats and took the prize. Newly-established admiralty courts condemned the taken vessels to the capturing captains. Small fortunes were made from a single lucky day at sea.

The Capture of the Venus

Privateering quickly eclipsed salt-making as the favorite activity of investors from across New Jersey and Philadelphia and more ships put to sea. Just to the south of Monmouth County, the village of Chestnut Neck, a few miles up the Mullica River from Little Egg Harbor (commonly called Egg Harbor at the time) became a privateering boomtown; Toms River in Monmouth County, smaller than Egg Harbor and lacking a direct overland road to Philadelphia, became the shore’s second privateer port. At least initially, the prizes captured by privateers and brought into Egg Harbor were small or middling vessels owned by middling Loyalists in New York—until the capture of the Venus.

On September 16, the Loyalist New York Gazette reported the capture of the Venus on the Jersey shore on August 26. "The ship Venus, [under] Capt. Chowne, was taken by two privateers…and carried into Barnegat." The report noted that Thomas Chowne was now confined in the Continental jail in Philadelphia. The privateer vessels were Chance and Sly from Philadelphia. It is unlikely that either of them carried more than 8 guns or crews larger than 30 men.

A week later, the Pennsylvania Packet reported again on the capture, noting that the Venus was unloaded at Egg Harbor. The Venus, bound for New York from London, was taken by privateer captain David Stevens of Philadelphia, seconded by privateer captain, Micajah Smith. Venus had "a very valuable cargo” that was further described:

[It] consisted of fine and coarse linen, calicoes, chinces, lawns and chambricks, silks and satins, silk and thread stockings, men's and women's shoes, a great variety of medicines and books, hardware, beef, pork, butter, cheese and porter, in short, the greatest variety of all kinds of merchandise.

The New Jersey Gazette advertised the sale of the Venus, “with cargo of fine cloth, satins, silks, shoes, medicines, books, beef and pork” at Egg Harbor on September 14. A second advertisement valued the cargo “in the amount to L20,000”—approximately the cost of ten midsized Monmouth County farm estates. The sale, however, did not occur because a New Jersey Admiralty Court had not yet condemned the prize to Stevens and Smith. Consequently, on September 23, the New Jersey Gazette advertised that an admiralty court would be held in Allentown on October 10 to hear Stevens’ and Smith’s claims to the vessel and its valuable cargo —as well as any potential counterclaims.

The delay was bad for Stevens and Smith and tragic for hundreds of others at Egg Harbor and Chestnut Neck. A massive British-Loyalist raiding party, more than 1,000 men, launched a punishing raid against the privateer base before the sale could occur. The raiders arrived in Egg Harbor in early October and burned eleven vessels and the village of Chestnut Neck. The details of the raid are the subject of another article, but importantly, retribution for the captured Venus was a key motivation for the raid.

The New York Gazette, on October 24, summarized the raid. It also noted that the raid aimed to avenge the capture of the Venus, "a very fine ship from London." The raiders destroyed the Venus and "11 sail of other vessels.” They also destroyed the warehouses holding the Venus’ cargo at Chestnut Neck. Lacking pilots who could navigate the large ship through the narrow river, they had to burn the ship rather than rescue it. If the Venus grounded in river on the way out, any British vessel behind it might be trapped.

Perspective

Why did the capture of the Venus prompt a reprisal when the capture of so many other vessels earlier in the year did not? There are likely two reasons: First, the Venus was larger than most or all of the vessels taken along the Jersey shore before it; it was the first time that a top-tier merchant vessel was taken. Second and likely more important, Venus’s cargo of British-made luxury items was a direct blow to British officers and the wealthiest Loyalists in New York. They were probably eagerly awaiting the ship’s landing and the chance to purchase luxury goods in short supply. New York’s most powerful men directly felt this capture. These men had the power to lobby British leadership to conduct the reprisal.

On the American side, the capture of the Venus was an important milestone. It marked the first time that regional privateers had taken a ship off the Jersey shore that could be labeled “a very fine ship from London.” It also appears to be the first time that relatively small privateers teamed up to capture a vessel that would have easily fought off either vessel as a single attacker. This lesson—hunting in small packs—would be used by privateers hovering in the sea lanes to and from Sandy Hook for the rest of the war.

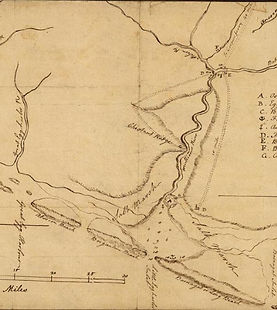

Caption: Two privateers captured the British ship Venus and brought it into Egg Harbor in September 1778. The map shows a narrow deep-water channel that needed to be used to carry in the big ship.

Related Historic Site: New Jersey Maritime Museum

Sources: Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 2, p 3395-6; Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; Franklin Kemp, A Nest of Rebel Pirates (Egg Harbor, NJ: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1966) pp 5-8.