The Death of the Pine Robber, Jacob Fagan

by Michael Adelberg

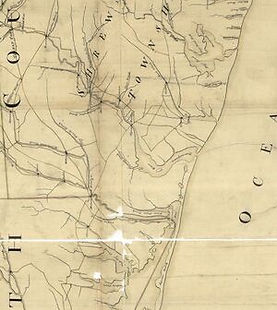

The first Pine Robber gangs, including that of Jacob Fagan, laired in the marshes between Shrewsbury and Manasquan. Fagan was only an outlaw a few months when he was killed by militia.

- September 1778 -

The Pine Robbers were Loyalist outlaws who lived in the coastal marshes and interior pine forests of Monmouth, Burlington, and Gloucester counties. While many of these outlaws made a living primarily by acting as middlemen in the illegal trade between disaffected farmers and the British commissary at Sandy Hook, others engaged in multiple violent robberies and burglaries.

A lot that has been written about the Pine Robbers is improbable and not supported by original documents. One account, for example, claims that Jacob Fagan’s Pine Robber gang had a sophisticated fortress-lair:

Fagan's gang had a state-of-the-art hideout in the pine barrens. Trap doors hidden under leaves and branches in steep hillsides admitted the pine robbers into 30 foot tunnels. These ended in storerooms that were large enough to hold six men. Buried beneath their floors was thousands of dollars worth of patriot loot.

Romantic depictions aside, living in swamps and subsisting off the occasional robberies of people who were, themselves, not wealthy, was a very difficult way to live. Fagan’s outlaw existence, which lasted only a few months, was not “state of the art.” Many Pine Robbers did not survive the war; of those who did, there is no reason to think they were anything other than poor at war’s end.

Historian David Fowler, who wrote the defining work on the Pine Robbers, traces their origin to early 1777 when some of the defeated Upper Freehold Loyalist insurrectionists hid in the woods after their insurrection was toppled. A few of these men were captured and jailed. Others may have stayed in the woods. These men laid low and convinced themselves that the British would return as liberators. But when the British Army traversed Monmouth County and quit New Jersey in July, 1778, any flickering hopes of liberation were dashed. Now, these Loyalist recluses mixed with British Army deserters and pre-war ne’er do wells. They emerged in outlaw gangs that have been imprecisely labeled Wood Rangers, Tory Banditti, and especially, Pine Robbers.

In June 1778, a dozen men received death sentences for treason, robbery, and burglary at Monmouth County’s Court of Oyer and Terminer—half were pardoned. Two of these Loyalists, William Dillon and Robert McMullan, either became Pine Robbers or consorted with them after their pardon. In August 1778, Major Richard Howell, from his camp at Black Point, wrote about marching after a Pine Robber gang to his south, but it is unclear if he ever did so. What is clear is that Pine Robbers gangs—swelled by deserters from the British Army—grew increasingly bold in summer 1778.

The Rise of Jacob Fagan and Attempts Take Him

Jacob Fagan was a criminal who was twice indicted for larceny before the war. In 1776, he stole a horse, and joined the Loyalist New Jersey Volunteers some time in 1777, probably shortly after the Loyalist insurrections were toppled. In the days before the Battle of Monmouth, Fagan and a few other Monmouth County Loyalists with the British Army, deserted and camped in the marshes a few miles inland from Shrewsbury. They became the core of the first notorious Pine Robber gang.

Fagan and his gang must have been active robbers in summer 1778 based on the many steps taken to counter him. Daniel Dey of the Monmouth County militia recalled in his veterans' Pension Application:

I volunteered for one month under Capt Walton at the time the British Army evacuated Philadelphia and marched through the State of New Jersey, was in the battle of Monmouth - was one week in the service under Col. [David] Forman hunting Tories through the pines, capturing more than 20 of them and fastened them together, two by two by the neck with a strong rope.

William Lloyd also recalled going "in pursuit of the Refugees of the Pines” in 1778. He further recalled that “they broke into the house of a man I knew and killed the man and his wife."

On August 10, with Fagan’s infamy building, the New Jersey Legislative Council (the Upper House of the legislature) asked Governor William Livingston to "order out one class of militia from each of the counties of Burlington and Monmouth, to be stationed in Monmouth” to protect residents from “the disaffected persons skulking in the pines." Two weeks later, Major Richard Howell, stationed at Black Point with a small guard of Continental soldiers, attempted to infiltrate Fagan’s gang and then proposed to attack them:

I sent out two men who pass for deserters to join the wood Tories, but could not join them, from their caution, having been deceived before. Since that measure was defeated, I now propose to go down by night & surround the swamp in which they are from, with this intelligence, and burn their cabins.

However, there is no evidence that Howell went after Fagan.

Fagan’s Most Notorious Incident and Death

The primary documented incident involving Fagan was the robbery of the house of Captain Benjamin Dennis. Amelia Dennis, the 15-year-old daughter of Captain Dennis, later recalled Fagan and Stephen Emmons (who used the alias “Burke”) and two others coming to the family home near Manasquan. Dennis was a target because he was a strong supporter of the Revolution and because he was holding money from a sale of a captured Loyalist vessel. Captain Dennis was not home when the Pine Robbers approached, but his wife and daughter were.

The first man to enter the house was a man named Smith, who, according to Amelia Dennis, was secretly an informer against Fagan. He warned Amelia to gather her father's valuables and flee into the woods. Amelia “hid a pocketbook containing eighty dollars in a bed-tick.” She and her little brother hid in the woods. Fagan and Emmons entered the house and became frustrated when they could not find any money. They found Rebecca Dennis, Amelia’s mother, and “took her to a young cedar-tree and suspended her to it by the neck with a bed cord” to force her to reveal the money's location. The potential hanging was disrupted by a passerby (John Holmes) who fled when the robbers descended on him. During the distraction, Mrs. Dennis freed herself and ran off. The robbers left with only a few household items.

Afterward, Captain Dennis moved his family to the village of Shrewsbury for safety. According to Amelia Dennis, Smith informed Captain Dennis of Fagan's plan to return to the Dennis home in order to more thoroughly search for the hidden cash. The militia set up an ambush and fired upon both Fagan and Burke when they came, but the Pine Robbers escaped. However, Fagan was apparently wounded and his body was recovered a few days later in a swamp. Fagan's body was brought to Freehold where:

The people assembled, disinterred the remains, and after heaping indignities upon it, enveloped it in a tarred cloth and suspended it in chains with iron bands around it, from a large chestnut tree, about a mile from the Court-house, on the road to Colt's Neck. There hung the corpse in mid-air, rocked to and fro by the winds, a horrible warning to his comrades.

Amelia Dennis’ full account is an appendix to this article.

Fagan’s death was reported in the New Jersey Gazette and Pennsylvania Evening Post.

Jacob Fagan, the chief of a number of villains of Monmouth County, terror of travelers, was shot. Since which his body was gibbeted on the public highway in that County, to deter others from perpetrating like detestable crimes.

The near-hanging of an innocent woman was an outrage that stirred the New Jersey Government. On September 30, the New Jersey Assembly, not knowing Fagan was already dead, concurred with a request from Governor Livingston:

To issue proclamations offering such reward or rewards as his Excellency and the Privy Council shall deem proper for the apprehension of Jacob Fagan and Stephen Emmons, alias Burke, and certain other disaffected and disorderly persons in the County of Monmouth, who have for the time past committed, and still continue to commit, diverse felonies & depredations on the persons & property of the inhabitants thereof.

The upper house of the legislature, the Council, recommended that Governor Livingston place bounties on the heads of: Jacob Fagan ($500), Stephen Emmons, alias Burke ($500), Samuel Wright of Shrewsbury, William Van Note, Jacob Van Note, Jonathan Burdge, and Elijah Groom ($100 each).

The New Jersey Gazette published the Governor’s proclamation accordingly on October 7:

Whereas it has been represented to me that a number of persons in the County of Monmouth, and particularly those herein mentioned, have committed diverse robberies, violences and depredations on the persons and the property of the inhabitants thereof, and in order to screen themselves from justice, secret themselves from justice in the said County: I have therefore thought proper, by and with the advice of the Council of this State, to issue this Proclamation, hereby promising rewards herein mentioned to any person or persons who shall apprehend and secure, in any gaol of this State, the following person or persons to wit: for JACOB FAGAN and STEPHEN EMMONS, alias BURKE, five hundred dollars each; and for SAMUEL WRIGHT, late of Shrewsbury, WILLIAM VAN NOTE, JACOB VAN NOTE, JONATHAN BURDGE and ELIJAH GROOM, one hundred dollars each.

The militia had already killed Fagan—so, Dennis and the other militia were ineligible to collect on his bounty. In November, Dennis petitioned for the Jersey Assembly for the bounty anyway. Governor Livingston was sympathetic to Dennis and wrote a letter on his behalf. Livingston noted that he could not give Dennis the bounty, but urged the Assembly to "recompense [Dennis’ party] for their risque and trouble as may be suitable encouragement for others to undertake the like enterprises."

On December 1, the Assembly voted to award Dennis £187 for his efforts—this amount was likely reimbursement for expenses related to mustering the militia to go after Fagan. The Council concurred on December 12, though it called the sum “a reward for taking Jacob Fagan” rather than reimbursement for expenses. This was less than the bounty on Fagan’s head, but still a significant sum.

Fagan’s death was re-reported in the New Jersey Gazette on January 29, 1779, after three other members of his gang (including Stephen Emmons) were killed. The newspaper wrote: "the destruction of the British fleet could not diffuse more joy through the inhabitants of Monmouth County then has the above deaths of these three most egregious villains." The death of Emmons is the subject of another article.

The death of the Pine Robbers was big news. It was reported as far away as Williamsburg, Virginia, where the Virginia Gazette reported on February 26:

We hear from East Jersey that a desperate gang of murderers, chiefly refugees, deserters from New York, were lately brought to condign punishment in a most striking manner. For months past these miscreants had plundered Monmouth County with impunity, all means used to curb their excesses being eluded, by their vigilance and sudden retreat to the pine forests. At length, however, they were way layed by a party of armed men, who put the whole to death.

However, other Pine Robber gangs led by Lewis Fenton, William Davenport, John Bacon and others would form and prove more destructive and durable than Fagan’s gang. The swamps of the Monmouth shore would remain, in the words of historian Donald Shomette, “lightly populated and altogether wild... the haunt of rowdies, smugglers, and highwaymen.” Pine Robbers would remain a significant problem for local governments and militia for the remainder of the war.

Related Historic Site: Bear Swamp Natural Area

Appendix: Amelia Dennis’ Account the Pine Robber Attack on Her Family

One Monday in the autumn of 1778, Fagan, Burke [actually Stephen Emmons], and Smith came to the dwelling of Major Dennis, on the south side of the Manasquan River, four miles below what is now the Howell Mills, to rob it of some plunder captured from a British vessel. Fagan had formerly been a near neighbor. Smith, an honest citizen, who had joined the other two, the most notorious robbers of that time, for the purpose of betraying them, prevailed upon them to remain in their lurking place while he entered the house to ascertain if the way was clear. On entering he apprised Mrs. Dennis of her danger. Her daughter Amelia, a girl of fifteen, hid a pocketbook containing eighty dollars in a bed-tick, and with her little brother hastily retreated to a swamp near. She had scarcely left when they entered, searched the house and bed, but without success. After threatening Mrs. Dennis, and ascertaining she was unwilling to give information where the treasure was concealed, one of them proposed murdering her 'No!' replied his comrade, 'let the d—d rebel b—h live. The counsel of the first prevailed. They took her to a young cedar-tree and suspended her to it by the neck with a bed cord. In her struggles she got free and escaped. Amelia, observing them from her hiding place, just then descried John Holmes approaching in her father's wagon over a rise of ground two hundred yards distant, and ran toward him. The robbers fired at her; the ball whistled over her head and buried itself in an oak. Holmes abandoned the wagon and escaped to the woods. They then plundered the wagon and went off. The next day Major Dennis removed his family to Shrewsbury under the protection of the guard. Smith stole from his companions and informed Dennis they were coming the next evening to more thoroughly search his dwelling, and proposed that he and his comrades should be waylaid at a place agreed upon. On Wednesday evening the Major, with a party of militia, lay in ambush at the appointed spot. After a while Smith drove by in a wagon intended for the plunder, and Fagan and Burke came behind on foot. At a given signal from Smith, which was something said to the horses, the militia fired and the robbers disappeared. On Sunday, the people assembled, disinterred the remains, and after heaping indignities upon it, enveloped it in a tarred cloth and suspended it in chains with iron bands around it, from a large chestnut tree, about a mile from the Court-house, on the road to Colt's Neck. There hung the corpse in mid-air, rocked to and fro by the winds, a horrible warning to his comrades."

Sources: Stephen Davidson, The Pine Barrens: Jacob Fagan's Gang, United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada, http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Trails/2012/Loyalist-Trails-2012.php?issue=201243; David Fowler, Egregious Villains, Wood Rangers, and London Traders (Ph.D. Dissertation: Rutgers University, 1987); John Raum, The History of New Jersey (Philadelphia: John Potter, 1872) v2,p72-4 Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), p196-7; Edwin Salter, Old Times in Old Monmouth (Freehold, NJ: Moreau Brothers, 1887) p 36; Donald Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast (Shiffer: Atglen, PA, 2015); National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Daniel Dey of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/#15489356; William Lloyd’s pension application contained in John C. Dann, The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980) pp 135-16; -- David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 83-4; Richard Howell to William Maxwell, George Washington Papers, Library of Congress, Series 4, Reel 5; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, September 30, 1778, p 180-1; David Bernstein, Minutes of the Governor's Privy Council, 1777-1789 (Trenton: New Jersey State Library, Archives and History Bureau, 1974) p 91-2; The Library Company, Pennsylvania Evening Post; Library of Congress, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; William Livingston to New Jersey Assembly, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 2, pp. 487-8; New Jersey Legislature notice, Monmouth County Historical Association, J. Amory Haskell Collection, folder 13, Document A; John C. Paterson, The Pine Robbers of Monmouth County, unpublished manuscript in the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association, 1834, p 3; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, p 54; Virginia Gazette, February 26, 1779,