The Loss of Tinton Falls

by Michael Adelberg

Lt. James Moody co-led a raid from Sandy Hook against Tinton Falls on June 10, 1779. The raiders captured five village leaders and 300 livestock. Afterward, the village was abandoned.

- June 1779 -

Through much of the Revolutionary War, a military frontier line stretched across northeast Monmouth County. On one side of that line was the British base at Sandy Hook, and on the other side was the New Jersey interior. In between was contested terrain, nominally-controlled by the New Jersey Government, but containing many disaffected residents and easily penetrated by Loyalist raiding parties. The village of Tinton Falls was in the middle of this contested stretch of land. Storekeeper Benjamin White wrote:

We were so near the line that in the fore part of the night we had the British and Refugees, in the morning the American troops. My brother was called a King's Man or Refugee and myself a rebel or friend of the Jersey troops.

Through early 1779, Continental troops were headquartered in Tinton Falls and a magazine of arms for the Shrewsbury Township militia was established there, in the barn of Colonel Daniel Hendrickson. However, an April raid by 750 British and Loyalist troops proved that the area was indefensible. As the Loyalist party entered the village, the Continentals assigned to defend the village retreated. The Loyalists burned a few of the village’s most prominent homes and, according to one resident, “behaved like wild or mad men” as they looted several buildings. Oddly, the raiders left the arms magazine intact.

A few weeks after the raid, George Washington ordered his troops out of Monmouth County and the people of Tinton Falls attempted to put their lives back together. With the Continentals gone, the New Jersey Legislature, on June 2, authorized raising a regiment of State Troops to defend Monmouth County and Colonel Asher Holmes started raising that regiment. But raising an appreciable number of men would take several weeks—in the meantime the military frontier line was undefended and the people of Tinton Falls would suffer a brutal raid just ten days after the Continentals departed.

Loyalist Accounts

Three British-Loyalist newspapers (two New York newspapers and the London Gazette) reported the raid against Tinton Falls. (The New York Gazette’s report is in Appendix 1 of this article). According to these accounts, a party of 56 New Jersey Volunteers and local Loyalist refugees assembled on Sandy Hook on June 9. They were led by Captain Samuel Hayden, Lieutenant James Moody, and Lieutenant Thomas Okerson of Shrewsbury "who was perfectly acquainted with the country."

The Loyalists landed at Jumping Point on the Shrewsbury River before dawn and advanced to Tinton Falls undetected. They divided into parties that surrounded the houses of the three militia officers who lived in the village: Colonel Daniel Hendrickson, Lt. Colonel Aucke Wikoff, and Captain Thomas Chadwick. In coordinated attacks, they captured the three officers. They soon captured Captain Richard McKnight and Major Hendrick Van Brunt who lived nearby. Loyalist newspapers described these men as “Tory persecutors” and claimed that McKnight had broken the terms of his parole from a prior capture by returning to militia service.

The Loyalists took all of the “publick stores,” the arms magazine, and some 300 cattle and sheep. With their captives and booty, they withdrew to Jumping Point. Thirty local militia, led by Lieutenant Jeremiah Chadwick advanced on the raiders as they loaded their boats. A hot one-hour engagement ensued during which Lt. Chadwick and Loyalist officers cursed each other and called out that no quarter would be granted to captives. Chadwick then “received two balls” and died. “Upon his falling, the Volunteers charged with their bayonets, drove the rebels and took possession of the ground." Casualty figures vary slightly across accounts, but the militia suffered either two or three dead, twelve or fourteen wounded; as many as seven additional men were taken prisoner. The Loyalists, who had the decisive advantage of bayonets in hand-to-hand fighting, lost one man with two wounded.

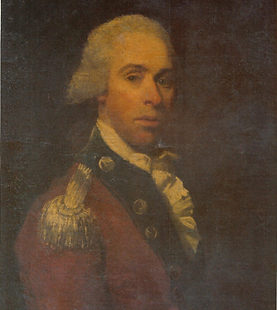

James Moody was a Loyalist from Sussex County who led a platoon of sixteen men during the raid. After the war, he wrote a self-aggrandizing autobiography that includes a narrative of the raid on Tinton Falls. He incorrectly stated that Loyalists took the militia officers "without destroying private property” but that they “destroyed a considerable magazine of powder and arms." Moody portrayed himself as leading the attack against the militia at Jumping Point. After running out of ammunition, “the bayonet was Moody’s only recourse, and this the enemy could not withstand; they fled leaving eleven of their number killed and wounded.” He reported that Lt. Chadwick died while uttering "bitter oaths of vengeance." After the militia was defeated, one of the rebels came forward with a handkerchief on a stick.” Moody then described his men’s withdrawal.

A truce was agreed on, the conditions of which were that they should have their dead and wounded, while Moody and his party were permitted to return to the British lines unmolested. None of Moody’s men were wounded mortally.

Moody reported that he sold his booty for “upwards of £500” and that “every shilling of which was given by Moody to his men for meritorious service."

Whig Accounts

The New Jersey Gazette reported briefly and incorrectly on the loss of Tinton Falls. The "party of Tories from Staten Island landed at Middletown in Monmouth County, plundered several houses and carried off four or five of the inhabitants prisoners." However, Philadelphia and Virginia newspapers reported more completely and accurately (even while under-reporting the prisoners and property taken):

A party of Tories landed at Shrewsbury Thursday last, when they were opposed by about thirty militia, hastily collected, who, after some resistance retired with the loss of two killed and ten wounded. As the Tories kept the ground, their loss is unknown. As soon as the militia had retired, they collected thirty horses, some sheep and horned cattle; took Colonel Hendrickson and a few of the inhabitants, and made off.

A receipt from Joseph Loring, British Commissary of Prisoners, from June 11 proves that the British accounts of the prisoners taken were correct. The receipt is a "List of Prisoners taken by the Refugees at Shrewsbury." It lists Daniel Hendrickson, Aucke Wikoff, Hendrick Van Brunt, Thomas Chadwick, Richard McKnight, and private Nicholas Van Brunt. Interestingly, a Maryland Continental, Private Abraham Irwin, was also taken. Maryland Continentals had been pulled out of Monmouth County ten days earlier—so Irwin was likely a deserter.

New Jersey’s Chief Justice, Robert Morris of New Brunswick, went to Tinton Falls shortly after the April raid to help rally the people of the village. He returned after the June 10 raid. On June 20, he wrote that the enemy “carried off” Col. Hendrickson, Lt. Col. Wikoff, Maj. Van Brunt, Capt. McKnight, and Capt. Shaddock [Chadwick]. He listed the livestock theft as “eighteen horses, 100 cattle & 50 sheep,” less than Loyalist accounts but still a huge loss for a single village. He described the battle at Jumping Point, claiming less than twenty militia engaged the retreating Loyalists. They "skirmished with and pursued them to the water, with more spirit than providence." Morris wrote that Lt Chadwick & Pvt. Hendrickson were killed and six militia were wounded. Morris also claimed that the Loyalists lost much of their booty: "Most of the sheep and some of the cattle drowned, and greater part of their plunder is lost, the water being so deep as to overset one and wash things out of the other." He claimed that the Loyalists released five prisoners on the beach because they lacked space on their boats.

Morris tried to reconvene the leaderless militia without success. He reported that the people of Tinton Falls were leaving the village:

Some are quitting their habitations and others declare they are willing to do so, observing that if they must go on by starving, they had rather do it in the country than the Provost Jail… they are but farmers and mechanics in middling circumstances, I have little hope of continuing it long.

Indeed, many of the women of Tinton Falls went west to Colts Neck where the local militia captain, James Green, provided for them. During the war, dozens of Monmouth Countians moved inland for safety.

Two of the militiamen who fought the raiders at Jumping Point, realled the battle in their postwar veteran pension applications. Elihu Chadwick, the younger brother of Thomas and Jeremiah Chadwick, recorded being with Jeremiah as he was killed. Oakey Van Osdol recalled:

Went to Monmouth Court House & from that down to Tinton falls where we were stationed to guard against the refugees at the time a company of Refugees came from sandy Hook Light House and landed at Black Point where Captain Jeremiah Chadwick with a company of men attacked them and they retreated below the bank down to the river and formed behind the Bank up the river & as Captain Chadwick advanced upon them they fired and killed him and killed some of his men.

The most vivid New Jersey account of the raid was provided by Eliza Chadwick Roberts, the daughter of Thomas Chadwick. She described the death of her uncle, Jeremiah:

My uncle, exasperated to the utmost pitch, followed the band and at daylight saw them already entering upon their boats to return to New York and discovered my father pinioned in one of the barges.

She wrote of her uncle advancing on the raiders, but that all but eight of the militiamen fled during the battle (they likely ran out of ammunition and lacked bayonets for the hand-to-hand fight). Chadwick advanced though his party “was constantly exposed to their fire without being able to return it." Jeremiah Chadwick was shot in the neck and then in the chest. A Loyalist, "fearing he would survive, flew to his side, drew his own sword from his scabbard and buried it in his heart.”

Antiquarian accounts add that Aucke Hendrickson, the brother of Daniel, accompanied Jeremiah Chadwick to Jumping Point and joined Chadwick in cursing the Loyalists. He survived the fight. Another source notes that private John Henderson was also killed by the Loyalists at Tinton Falls. An 1846 letter suggests that a small Loyalist party attacked nearby Shrewsbury and defeated a twelve-man guard of lingering Continentals at the same time that Tinton Falls was razed. (See Appendix 2.)

The sacking and loss of Tinton Falls was a small military event, but a climatic one for the people of the village. Afterward, the village was abandoned. The raid moved the militia frontier line westward to Colts Neck for at least a year.

Related Historic Site: Sandy Hook Lighthouse

Appendix 1: New York Gazette account of the attack on Tinton Falls

On the 9th day of June instant, a party of volunteers went down to Sandy Hook, where they were joined by a small detachment of Col. Barton’s regiment of New Jersey Volunteers, from where they proceeded to the Gut, about four miles distant, but as the wind blew very hard, the boats that were to be provided did not come in, and they were obliged to return to the Light House. On the 10th, being ready to leave the Gut, it was agreed by the party that Lieut. Okerson, who was perfectly acquainted with the country, should give them direction. They advanced undiscovered with fifty-six men, as far as Fenton [Tinton] Falls, about ten miles from the landing, where they halted just as the day broke, near the rebel headquarters at the back of the town, but not knowing the house where their main guard was kept, they determined to surround three houses at the same time. Capt. Hayden, of General Skinner’s, proceeded to the house of Mr. McKnight, a rebel Captain; Ensign [James] Moody to the house of Mr. Hendrickson, a Colonel; and Lieutenant Throckmorton to one, Chadwick’s, a rebel Captain. The three parties came nearly at the same time to the place where the main party of the rebels was kept but missed them, they being on a scout. They made Col. Hendrickson, Lieut. Col. Wikoff, Capts. Chadwick and McKnight, and several privates, prisoners; after proceeding one mile further took Mr. Van Brunt. They collected about three hundred sheep and horses belonging to the rebels. A warm engagement ensued at Jumping Inlet [Shrewsbury Inlet], and continued an hour, where they heard the Captain of the rebels declare that he would give them no quarter, and soon after he received two bullets, whereupon his falling, the Volunteers charged with the Bayonets, vanquished the rebels and took possession of the ground where the dead and wounded lay. When they had crossed the river, they observed a man with a flag riding down from the rebels, who asked for permission to carry off the dead and wounded, which was immediately granted. The man with the flag informed them that the whole of their party there was engaged were killed or wounded. They returned to Sandy Hook the same evening with their prisoners and a quantity of livestock, &c. The names of the men who engaged the rebels are as follows: --Captain Samuel Heyden, Lieut. Thomas Okerson, Lieutenant Hutchinson, Ensign Moody, first battalion General Skinner’s, Lieutenant John Buskirk of Colonel Ritzema’s, five privates of General Skinner’s; two sailors and a coxswain of one of the boats, Marphet [Morford] Taylor, William Gillian, John Worthley, volunteers. In the engagement, one officer and two privates of the volunteers were wounded.

Appendix 2: June 1779 – The Allen House Massacre

The Allen House was the most prominent tavern in the village of Shrewsbury. It had hosted the key town meetings in 1775 in which the Loyalist-leaning residents of the township resisted and then acceded to join the Continental movement. As the war commenced, the village of Shrewsbury sat on the military frontier line. The village was nominally under the control of the Continental and New Jersey governments, but it could not be defended against Loyalist partisans on nearby Sandy Hook. Many locals lived as neutrals—maintaining relationships with both militaries.

In 1779, small parties of Continentals were stationed in the village of Shrewsbury. According to a letter written by Lyttleton White in 1846, a 12-man guard, under a Lieutenant was stationed at the Allen House in the summer of 1779 “to watch the movements of the Tories.” A small Loyalist raiding party set their sights on the Allen House:

Five of the Tories or Refugees came in a boat up a branch of South Shrewsbury River - landed and under cover of woods hedges and etc. - got the south side of the Episcopal Church about 6 rods from the above said house - the party being headed by Joseph Price and Richard Lippincott.

From nearby bushes, the Loyalists spied on the tavern. The Continentals were remiss in protecting themselves. The Loyalists “found no sentries set and [the soldiers] lounging about, not under arms.” Seeing this, the Loyalists attacked:

Price then ordered his party to fix their bayonets and started on full run for the house, where the troops was quartered - their arms all stood together in the North room - one of Price's men grabbed them all in his arms - A scuffle took place being 12 [Continental soldiers] to 5 of the Refugees - the man who held fast on the guns of the American troops was thrown but held fast. They put the bayonet through one of the 12 and he fell at once on the floor - and run two more of them through, the Lieutenant then surrendered.

The twelve-man guard was thoroughly defeated by the smaller Loyalist party: “one of the two last killed got out into the road, his bowels coming out, he soon died; the other one got somewhat farther off and fell and likewise died - [The raiders] took the other 9 prisoners - broke their guns round a Locust tree, and made their escape.”

Locals presumably had the ability to spot the Loyalist raiders and alert the Continentals before the attack. But the residents of Shrewsbury village were known to be largely disaffected, and their disaffection for the Continentals was likely enhanced by provocations from the soldiers. An antiquarian source claimed that the Continental troops stationed in Shrewsbury created mischief in the village: Several took target practice at the iron crown atop the Shrewsbury Christ Church (the crown was a symbol of the British monarchy). The soldiers did not dislodge the crown, but did put several shots into the church. On another occasion, a soldier set fire to the church. An alert local Quaker, William Parker, extinguished the fire.

The tavern’s pre-war owner was Josiah Halstead, but he had fallen into debt and creditors turned him out in 1779, when William Lippincott began managing the tavern. Lippincott purchased a Loyalist estate in April 1779 and was a vestryman at the (Anglican) Christ Church, as it steered away from the Loyalism of its former minister, Samuel Cooke. So, Lippincott might have been targeted by local Loyalists. Interestingly, Joseph Price had married Halstead’s daughter, Amelia Halstead. So, Price likely knew the tavern well and the raid may have had a familial-revenge angle.

Lyttleton White’s letter also narrates a second, related, event:

In the year and summer, 1779, a party of Refugees landed at Jumping Point – 6 miles east from the village of Shrewsbury, about 25 in number, and made their way as far up as Tinton Falls, collecting and driving off as many cattle as they could - The above party landed by the above Joseph Price. Captain Jeremiah Chadwick, being informed of it, collected all the men he could as well, some few troops on duty, and formed them about 2 miles east of Shrewsbury village, came within shooting distance and kept up a firing on long shot, the Refugees still driving the Gut.

It is probable that this event occurred concurrently with the attack on Allen House. The details regarding Jeremiah Chadwick rallying the local militia are similar to what other sources report about Chadwick on June 10, 1779, when Tinton Falls was destroyed by Loyalist raiders.

Skepticism about the Allen House Massacre

The Allen House Massacre is documented in just a single source, Lyttleton White’s letter, and that source was written in 1846, decades after the fact. According to White, Joseph Price came back to Shrewsbury after the war and talked about the raid with White and others and the raid. Given the thin documentation, there is some reason to question the Allen House Massacre and consider whether it should be treated as a real event.

This author believes that the Allen House Massacre should be treated as a real event because the essential facts detailed in the 1846 letter are corroborated in other sources. These include:

Continental soldiers were stationed in the village of Shrewsbury in 1779;

Continental soldiers stationed in Shrewsbury Township were ill-disciplined and vulnerable to attack and capture;

Small Loyalist raiding parties were active in northeast Monmouth County in 1779;

Joseph Price and Richard Lippincott, named by White, were active Loyalist raiders;

At least three Shrewsbury Loyalist raiders—Price, Clayton Tilton, and Joseph Paterson—returned to Shrewsbury Township after the war;

A party of seven men quartered in Shrewsbury village was taken and captured on January 12, 1780 (establishing a likelihood that similar events occurred nearby).

The Allen House Massacre was a small military clash. But it was exactly the kind of nasty, little event that characterized the Revolutionary War in Monmouth County from 1779 through 1782. A number of events that are the subject of articles in this series, including the remarkable court martial of the Loyalist Jacob Wood and the bold prison escape by John Hewson, are documented in only one source. On balance and with appropriate qualifiers, the Allen House Massacre should be interpreted as a real event.

Sources: Benjamin White quoted in Judith M. Olsen, Lippincott, Five Generations of the Descendants of Richard and Abigail Lippincott (Woodbury, N.J.: Gloucester County Historical Society, 1982) pp. 159-61; Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application of Oakey Vanosdol, National Archives, p4-9; Autobiography of Eliza Chadwick Roberts, coll. 215, Monmouth County Historical Association; United Empire Loyalists, Loyal Directory: http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info; Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; Library of Congress, Early American Newspaper, New Jersey Gazette, reel 1930; Moody’s narrative printed in Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), p207; William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 404-5; Susan Burgess Shenston, So Obstinately Loyal, James Moody (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2000) p64; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, p 429; James Moody, Lieut. James Moody's Narrative of His Exertions and Sufferings in the Cause of Government, Since the Year 1776 (Gale - ECCO, 2010) pp. 10-2; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 3, pp. 441, 456-7, 475; The London Magazine (London: R. Baldwin, 1780) p349-50; Autobiography of Eliza Chadwick Roberts, coll. 215, Monmouth County Historical Association; Virginia Gazette, July 3, 1779; Munn, David, Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey, (Trenton: Bureau of Geology and Topography, New Jersey Geological Survey, 1976) p 140; Morris, Robert, “Letters of Chief Justice Morris, 1777–1779,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, vol. 38 (1920), pp. 175-6; Munn, David, Battles and Skirmishes of the American Revolution in New Jersey, (Trenton: Bureau of Geology and Topography, New Jersey Geological Survey, 1976) p 65; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Elihu Chadwick; Prisoner Receipt, William Clements Library, Henry Clinton Papers, vol. 60.

Allen House Massacre Sources: Lyttleton White, "The Allen House Massacre", Monmouth County Historical Association Newsletter, vol. 1, 1973, January 1973, p 1; Lyttleton White to Daniel Veech McKean, Monmouth County Historical Association, Subjects Alphabetical, #98; The Allen House, unpublished manuscript in the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association, January 2012; Gustav Kobbe, The New Jersey Coast and Pines (Forgotten Books, 2015) p 28; Margaret Hofer, A Tavern for the Town: Josiah Halstead's Community and Life in Eighteenth Century Shrewsbury (Freehold: Monmouth County Historical Association, 1991) p 14; Beck, Henry Charlton, The Jersey Midlands (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1939) pp. 345-346; Howard Peckham, The Toll of Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974) p 67.