Militia Family Suffering After the Battle of Navesink

by Michael Adelberg

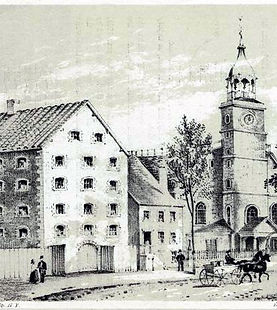

The Sugar House warehouse in New York was converted into a prison that held roughly 500 prisoners. Most of the militiamen captured at the Battle of Navesink were confined here.

- February 1777 -

By 1777, both the British and Continental governments were struggling to house and feed thousands of captured enemy combatants. The British Army in New York City was faced with the acute problem of holding 4,000 prisoners in a city that was already overcrowded with British troops and Loyalist refugees. Lacking alternatives, the British converted old warehouses and non-seaworthy ships into improvised prisons.

These impromptu prisons were horrible places where hundreds died from inadequate food, shelter, and clothing. American prisoners had few beds and blankets. The skimpy twice-a-week prisoner rations (1/2 lb. of biscuit, 1/2 lb. pork, 1/2 pint of peas, cup of rice, 1/2 oz. butter) was rarely fully allotted. Following the defeat at the Battle of the Navesink, more than 70 Monmouth militiamen were put into these miserable jails.

Monmouth Militiamen in British Prisons

Historian Edward Raser studied 72 Monmouth militiamen captured at the Battle of Navesink. Five died in jail within two months and five others died in prison over the next year. At least seven of these men were married and at least four were fathers. Two of the prisoners were paroled from jail to become tailors for the British Army. The captured officers (Capt. Barnes Smock, Lt. Joseph Brown, Lt. Thomas Cook, Lt. James Whitlock, Ens. Tobias Polhemus) were eventually paroled to private homes on Long Island.

Several of the captured militiamen discussed their time in prison in their postwar veteran’s pension applications after the war. Garrett Wikoff recalled his eighteen months of confinement:

Together with about seventy other persons, were taken prisoner and carried on board a 64-gun ship then lying near Sandy Hook where he remained three days and three nights closely confined in her hatches. He was then taken, together with his comrades, to New York and imprisoned in the Old Sugar House, as it was then called. He remained there a prisoner to the enemy until the 8th of August 1778.

Other Monmouth militiamen offer similar narratives. A few additional details are offered below:

James Morris: “he was very sick with small pox, and looked very miserable, his hair was nearly all off his head."

Cornelius Vanderhoff: "detained for 18 or 20 months until there was little number [left alive], for want of humane treatment”

Matthias Hulse: “confined to the Old Sugar House… remained a prisoner there from the time he was taken, in close confinement, until the 12th day of May, when he was exchanged”

Linton Doughty: “was confined for 19 months - for this time, on his return home received pay."

Henry Vunck: “suffered while a prisoner great privations… in poor clothing and scanty & unwholesome provisions. Many of the prisoners died in consequence of this treatment.”

Elisha Clayton may have had the most interesting recollection. He was “compelled to work at his trade in making clothes for the enemy; while thus employed he watched [for] his opportunity and made his escape, accompanied by a British soldier whom he induced to desert from the enemy.”

Attempts to Support the Prisoners

The Continental Commissary of Prisoners, Elias Boudinot, sought provisions for the prisoners of war. He engaged John Covenhoven, formerly Monmouth County’s leading delegate in the New Jersey Assembly prior to capture by a Loyalist party on November 30, 1776. Covenhoven signed British protection papers and, after that, he retired from public life. But raising provisions for prisoners of war at Boudinot’s request brought him back into a leadership role. Boudinot wrote Covenhoven on January 17, 1778:

I must again beg that you will exert yourself on this occasion, and add a few quarters of beef (say 10 or 12) and 100 bushels of Indian corn -- I enclose two passports for the sloop, and most heartily wish she may go off on the first open weather.

Boudinot promised to pay for the provisions that could be raised. Covenhoven’s response has not survived but it was apparently encouraging because Boudinot directed an associate, "I hope you will soon receive a boat load of flour from Middletown Point."

Covenhoven further responded on January 30:

I have purchased a quantity of wood which is this day setting out for New York with a few lbs. of flour; I have also engaged a quantity of wheat… will be ready when the boat returns. The beef you desired to be sent I have not got & will be difficult to be had; purchased between two & three hundred bushels of rye.

Covenhoven noted delays with shipping these goods to the prisoners in the winter because "the boat was froze up" at Middletown Point.

Paroled Officers and the Special Status of Capt. Barnes Smock and Lt. James Whitlock

Consistent with the social class-focused attitudes of the day, special attention was given to the captured officers. Several were paroled from prison to private homes on Long Island. However, two of the officers, Captain Barnes Smock and Lt. James of Whitlock, were denied this lenient treatment for several months because they had signed British protection papers during the Loyalist insurrections.

The harsh treatment of Smock and Whitlock caught the attention of Elias Boudinot. In December 1777, Boudinot compiled a report to Congress titled, "State of Charges Against the Prisoners in the Provost of New-York.” It included this paragraph:

Captain Smock and Whitlock discussed entering the service after taking oaths of Allegiance last winter to the King of Great Britain. They acknowledge the fact, declaring their faithful adhesion to their oaths as long as protected, but when the English left the Jerseys, they took the benefit of General Washington's proclamation. If this is a crime, it was equally so in the first instance, after submitting to our Government.

Boudinot was not successful in negotiating parole for Smock and Whitlock. In March 1778, he wrote George Washington about Smock and Whitlock and a few other captured New Jersey officers who were denied parole on Long Island. “That having repeated my Applications for the relief of the seven remaining Officers in the Provoost, I could not succeed, and as the objections against the liberation of Smock, Whitlock and Skinner are rather trifling,” Boudinot called for a general prisoner exchange as the best way to help these men.

The next month, April 1778, Boudinot and his British counterpart negotiated a "Draft of the Proposed Cartel for Prisoner of War Exchanges." That document lists eleven officers, including Smock and Whitock, who “remain yet unexchanged” as "the objects of particular exception” The cartel proposed to move these eleven men to the top of the list of men to be exchanged:

We do hereby specially stipulate and declare, that the aforesaid officers shall be immediately exchanged on the terms of this cartel, for any officers of equal rank, or others by way of equivalent or composition; which have been or shall be delivered in lieu of them.

The draft cartel was not immediately executed, but it appears to have helped Smock and Whitlock. A “List of Whig Officers on Parole on Long Island” compiled by Boudinot in August 1778 includes Smock and Whitlock as paroled in Brooklyn. Other documents related to the paroled officers corroborate this.

The officers paroled to Long Island received vastly better treatment than the rank & file left in the British prisons, but parole was not without insults and dangers. Two Monmouth militia officers paroled on Long Island, Thomas Little and Tobias Polhemus, petitioned British general James Pattison on August 29, 1778, about “daily and repeated insults” from British troops:

This treatment we bore with patience, but...they continued and their brutality [and] carried them so far as to beat us in a cruel manner. They openly declared that they came to our quarters with a formed design to perpetrate these violences and that they were determined to murder us.

Attempts to win the exchange of these paroled officers failed more often than not. Lt Thomas Cook, a prisoner on Long Island, wrote to Nathaniel Scudder in August 1780:

My brother informs that Lewis Thomson was sent here to effect an exchange, it has answered no valuable purpose to that end, the influence of such men is very little in this place. Had he been of my rank, it is possible it would have been done... I am at a loss to know the reasons why an exchange do not go on for me, the officers in general are in a very disagreeable circumstance [sic]; it is fifteen months since our bond was paid [permitting parole to Long Island] or the last Public supplies were sent to us.

Edward Raser noted that the first five militiamen were exchanged in May 1777, probably due to serious illness. Most of the Monmouth prisoners came home as part of the general prisoner exchanges conducted in the summer of 1778. Once exchanged, Barnes Smock returned to the militia as captain of his Middletown company; he was captured again by Loyalist raiders in May 1780. James Whitlock was listed in a 1778 prisoner schedule as “broke parole.” For this offense, he was not exchanged until December 1780. He was probably very ill and died soon after this release.

New Jersey Government Provides Relief to Families of Some Captured Militiamen

New Jersey leaders sought to help the prisoners and their families. On September 20, 1777, David Forman petitioned the New Jersey Legislative Council for ongoing militia wages to the families of men captured at the Battle of the Navesink; the Council approved the petition on the same day, but apparently lacked the power to appropriate funds.

So, in November 1777, Asher Holmes and Nathaniel Scudder petitioned the New Jersey Assembly "setting forth that a great number of militia of the county of Monmouth under their command have at different times been taken prisoner by the enemy, some of whom have perished in confinement, and other in their family are in great distress." They requested relief for the suffering families. It does not appear that the Assembly acted on the petition.

However, in March 1778, the New Jersey Council of Safety, on which Scudder served, "Agreed, that there be paid to Col. Asher Holmes, the sum of £120 -- for use of the wives, widows and children, of such militia inhabitants of Monmouth County, who have either been taken prisoners by the enemy or killed in battle, & who appear objects of public charity, to be distributed among them at [his] discretion." Holmes received £120 for the relief of the following "suffering families": James Hibbetts, Peter Yateman, Samuel Hanzey, John Bowes, Abraham Marlat, Nathan Marion, Joseph Davis, William Norris, William Cole, Alexander Clark, Lambert Johnson, and Obadiah Stillwell. Why the families of these men merited relief while others did not was not stated.

In June 1781, the New Jersey Assembly returned to the Battle of Navesink. On June 4, it voted 29-1 to give James Whitlock legal title to the estate of his brother, John Whitlock. The next day, the Assembly voted half-pay pensions (£2 S5 per month) to the wives of five men killed at the battle. They were:

Isabella Hibbetts [widow of James Hibbetts],

Mary Stillwell [widow of Obadiah Stillwell],

Elizabeth Cole [widow of William Cole],

Mary Winter [widow of James Winter], and

Penelope Davis [widow of Joseph Davis].

Perspective

By any measure, the Battle of the Navesink was the worst moment of the war for the Monmouth militia and many of the seventy-two men captured and their families suffered for years afterward. However, many other militiamen and their families suffered from militia service at other times for other reasons. A few examples are offered below based on postwar pension application narratives:

Job Clayton: “His four older brothers were made prisoners by the refugees and confined many months in the Sugar House, at the City of New York.”

William Johnson: "My father, a Whig, was robbed of between five and six pounds of hard money. I myself, was robbed of thirty pounds and my coat, vest and even my shoes.”

Rachel Lake, regarding the service of her dead husband, John Smith: “She lost a child in his absence… They were robbed and plundered by a party of Tories one time during the war, and upon another occasion they were robbed of about twenty sheep, which were also driven off by the Tories."

Rebecca Shepherd, wife of Captain Moses Shepherd (in the application of John Truax): "She was informed that the enemy intended to take her off, this information caused her to leave her home at night… the refugees took the slay [sic] & horses and brought them off to Sandy Hook."

Altche Sutphin, regarding the service of her husband, Derrick Sutphin: “He was called out the same week as the wedding… when a fellow soldier by the name of William Thomson was killed on Middletown Highlands… The wedding party dared not remain overnight at the house, but dispersed early in the evening for fear of the Tories who would be upon them - that the bride remained at his house while the groom, the said Sutphin, was called out in the service."

Mary Wall, regarding the service of her husband, James Wall: “She was sometimes left with small children and such assistance as could be secured in the affected state of the country exposed to the ravages of a cruel enemy without any male about the house… the enemy were always willing to make daring inroads into the county to capture those who were obnoxious to them or plunder their houses."

Asa Woolley: "He suffered from the cold, his feet were frozen, his eyes much injured, so that he was not able to read for seven years. The injury arose from the flash of a gun when fighting the Enemy... he obtained a furlough from Captain [Richard] McKnight to visit his friends but in a few nights his comrades were taken prisoner, and carried to New York."

Related Historic Site: The Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument (Brooklyn)

Sources: Ammerman, Richard, “Treatment of American Prisoners during the Revolution.” New Jersey History, vol. 78 (1960), pp. 263-5; Edward Raser, "American Prisoners Taken at the Battle of the Navesink," Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, vol. 45, n 2, May 1970; William Smith, Historical Memoirs of William Smith: From 26 August 1778 to 12 November 1783 (New York: Arno, 1971) p 321 note; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Cornelius Vanderhoff; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Job Clayton; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Linton Doughty; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Joseph Van Note of Ohio, S.11617; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Elihu Clayton; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Eldridge; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Matthias Hulce; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Garret Wikoff of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/# NJ 28142503; Receipt, National Archives, Revolutionary War Rolls, Coll. 91, p195; Journals of the Legislative Council of New Jersey (Isaac Collins: State of New Jersey, 1777) p111; John Fell's Journal, Brooklyn Historical Society, coll. 1974.225; Elias Boundinot to Congress, Library of Congress, Peter Force Collection, 7E, reel 3, Elias Boudinot Papers; Elias Boudinot to John Covenhoven, Elias Boudinot Letterbook, Wisconsin Historical Society, p63-6; Princeton University Library, CO230, Elias Boudinot to John Covenhoven; List of Officers, New Jersey State Archives, Dept. of Defense, Revolutionary War, Numbered Manuscripts, #3994; Minutes of the Provincial Congress and the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey 1775-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 2009) p 214; Elias Boudinot to George Washington, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 14, 1 March 1778 – 30 April 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004, pp. 16–24; Elias Boudinot, The Elias Boudinot Letterbook (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2002) p114; Draft Prisoner Cartel, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 1, 1768–1778, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961, pp. 466–472; List of Prisoners, New Jersey State Archives, Dept. of Defense, Revolutionary War, Numbered Manuscripts, #3967; List of Prisoners, National Archives, Collection 881, R 593; Rufus Lincoln, The Papers of Captain Rufus Lincoln, ed. by James M. Lincoln. (Cambridge, MA 1903) p. 29-40; Samuel B. Webb, Correspondence and Journals of Samuel B. Webb (NY: Arno, 1969) v2, p123; List of Captured Officers, National Archives, Collection 881, R 593; Elias Boudinot, Accounts for Prisoners, New Jersey State Archives, Dept. of Defense, Revolutionary War, Numbered Manuscripts, #3976; Thomas Cook to Nathaniel Scudder, National Archives, Papers of the Continental Congress, reel 93, item 78, vol. 5, #499; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, September 14, 1780, p 258; Thomas Little and Tobias Polhemus, Memorial, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Irvine-Newbold Papers, box 77, folder 29; List of Suffering Families, New Jersey State Archives, Dept. of Defense, Revolutionary War, Numbered Manuscripts, #1148; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, November 22, 1777, p 28; Minutes of the Provincial Congress and the Council of Safety of the State of New Jersey 1775-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Library, 2009) p 214; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, May 22 and June 4, 1781, p 8-32; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, June 5, 1781, p 34; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Asa Wooley; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Smith; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, James Wall of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/# 20365758; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - William Johnson; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Truax; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Derrick Sutphin.