The Rise of Little Egg Harbor and the British Response

by Michael Adelberg

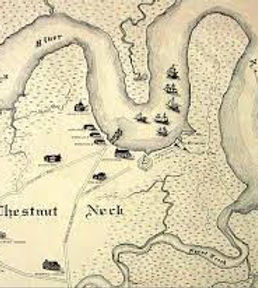

This map shows the winding Mullica River that connected the village of Chestnut Neck to Little Egg Harbor. It would become New Jersey’s most important Revolutionary War port.

- July 1776 -

By spring 1776, there had already been a handful of incidents involving British ships on the Jersey shore, including the capture of a British storeship in January intended for their army. An enormous fleet departed England, bound for America with 25,000 soldiers. It would be the largest European Army to ever land in the Americas.

As New York City became rebellious, the squadron of British ships at New York sailed for Sandy Hook and seized it as a naval base—it would be held by the British navy longer than any piece of the Atlantic Seaboard. More British navy vessels arrived in American waters—and the British blockaded the major American ports in April. Philadelphia ships were blocked from entering the Delaware Bay. They diverted to Little Egg Harbor to avoid capture.

The Rise of Little Egg Harbor

Located immediately south of Monmouth County, Little Egg Harbor, and the inland village of Chestnut Neck, a few miles up the winding Mullica River, had long been part of Philadelphia’s economy. The Delaware River froze for parts of each winter and ships went to Little Egg Harbor (called “Egg Harbour” at the time) to reprovision and deposit cargo for overland transport. When the British blockaded Delaware Bay in April 1776, it was only natural that Philadelphia ship captains detoured to Little Egg Harbor.

The Continental Congress, based in Philadelphia, embraced the New Jersey port. Its journals record more than a dozen references to activity there between April 1 and July 31. The Congress sent agents to Egg Harbor, received prisoners there, transported war materials, fitted out vessels, and sent wagon-trains back and forth from Philadelphia. In June, Congress considered the need to defend the port. It resolved: "The Marine Committee be empowered and instructed to build, man and equip two large row gallies for the defense of Little Egg Harbour." But there is no evidence that these gallies ever put to sea.

Newspapers describe at least seven vessels coming into Egg Harbor in seven weeks. They are summarized in the table below:

Date / Vessel / American Captain / Other Information

April 22

British “tender”

Capt. John Barry

Takes six-gun schooner, tender to the HMS Phoenix

May 5

Sloop

Capt. Youngs

Brings in cargo of “13 tons of powder, 24 tons of salt petre, and 60 arms”

May 18

Schooner Fidelity

Capt. Broadhurst

New Jersey vessel chased by British vessel, crosses into Egg Harbor to escape

June 5

Three prizes: Lady Juliana, Juno, and Reynolds

Capts. George McEvoy and John Adams

Two American privateers, Congress and Chance, bring in three prizes with “cargo of 187 lbs. of plate, 1000 hogshead of sugar, 246 bags of pimento, 396 bags of ginger, 25 tons of cocoa, 1 cask to turtle shells.”

June 6

“small privateer”

Unknown

Cargo of “1100 hhds Sugar, 140 Puncheons Rum, 70 Pipes Madeira, 24000 Mexico Dollars”

It can be safely assumed that additional ships entered and left the port during this period.

British Warships Patrol the Jersey Shore

The increased traffic at Little Egg Harbor and necessity of maintaining a presence at Sandy Hook and the Delaware Bay led to British warships traversing the Jersey Shore. In April, an anonymous New Yorker wrote about the effectiveness of the increasing Royal Navy activity:

They are driving back all the boats from the Jersies and cutting off all our supplies and provisions… [but] it is impossible that the Men-of-War can watch all our vessels, though they lie at the Hook on that purpose; we have so many creeks and harbors that they know nothing of, that they cannot ruin us.

The first prize taken by a British vessel on the Jersey shore might have been on April 1 when a British tender to a frigate “took a small sloop, then lying in the road, belonging to Egg-Harbor." Large British warships were frequently “tended” by sloops that ferried men and provisions in and out of shallow ports that the larger ships could not enter. The shallow, unmarked ports of the Jersey shore were dangerous to British frigates, so tenders were especially valuable for shore activity.

Two weeks later, another tender took on a local pilot at Barnegat. The Pennsylvania Journal reported: “One Arthur Green of Barnegat was taken by the Phoenix's tender and has given Capt. Parker an account of all the inlets about there.” The report noted that Green was now on a Loyalist sloop “which they have fitted out as an armed vessel, which, make no doubt, he will be cruizing in all the inlets." This appears to be the first reference to Loyalist privateering on the Jersey Shore.

In May, the New York Provincial Congress noted that "Captain Jonathan Clarke, late from the French West-Indies… had the misfortune to have his vessel and cargo seized and taken by an armed tender near Black-Point, below Sandy-Hook.” The legislature advanced $25 to assist Clarke and his crew for their hardship. A few days later, Commodore Esek Hopkinson of the Continental Navy wrote of the sloop L'Amiable Marie being taken off the Shrewsbury shore by HMS Phoenix. He noted that sailors on board the sloop were pressed into the British Navy.

The British Navy chased another vessel south of Sandy Hook on June 12. The Pennsylvania Ledger reported:

A sloop belonging to New Brunswick from Curacao was drove ashore by one of the ministerial pirates a little southward of Shrewsbury. The crew got on shore and by assistance of the country people [and] drove the pirates off. Her cargo consists of dry goods and about 300 bushels of salt, which is safely landed.

The British naval presence at Sandy Hook continued to grow, from three warships in April to seven in May, to twelve in early June. Patrols of the Jersey shore continued. On June 23, the New York Journal reported, "the enemy's ships were all on a cruise along the [Jersey] coast” and they apparently destroyed an American vessel, “the schooner that was burnt belonged to Egg Harbor." The British armada arrived at Sandy Hook on June 29.

The British cruised the Monmouth shore without significant opposition. The Continental Navy had vessels around Cape May and scored a few victories against the British Navy. But Continental Navy vessels did not come north to the Monmouth shore until the end of 1776. In the meantime, the New York State Navy assigned two small vessels to patrol the shore north of Little Egg Harbor, but it appears that these vessels spent more time avoiding larger British warships than protecting American ships.

Joseph Galloway, a leading Loyalist, wrote about the vulnerable New Jersey shore. New Jersey’s ports were "for the most part, naked, without fortifications and cannon." Little Egg Harbor was “altogether defenceless" and its vessels “stay in harbor" when British ships are nearby. He wrote to Admiral Richard Howe, commanding the British Navy in America, that "no privateer could pass out of any port… without your consent." Yet the British were not interested in moving against the small villages and shallow ports on the Jersey shore in 1776.

Two years later, the British would regret their failure to move against Little Egg Harbor early on. It would blossom into a center of American privateering. The port of Toms River, 30 miles north in Monmouth County, would emerge as New Jersey’s second most important privateer port.

Related Historic Site: Tuckerton Historical Society

Sources: Margaret Willard, Letters on the American Revolution 1774-1776 (Associated Faculty Press, 1968) p 308; Joseph Galloway, Letter to the Right and Honourable Viscount Howe on His Naval Conduct in the American War, (London: J. Wilkie, 1779) pp. 15-19, 21-22, 24, 35-7; William James Morgan, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1969) vol. 5, p 713. Robert Scheina, "A Matter of Definition: The New Jersey Navy, 1777-1783," American Neptune, 1979, vol 39, n 3, p 211; Journals of the Continental Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/05000059/ v4, p293; 328, 351 and 379; v5 p445, 476, 722, 729; Donald Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast (Shiffer: Atglen, PA, 2015) pp 51-60; Donald Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast (Shiffer: Atglen, PA, 2015) pp 59-60; Peter Force, American Archives: Documents of the American Revolution, 1774-6 (digitized: http://dig.lib.niu.edu/amarch/find.doc.html), v5: p 745 and v6:1323; William James Morgan, Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1969) vol. 6, p 650 and vol. 5, p 698; Alverda S. Beck, ed., The Correspondence of Esek Hopkins (Providence, 1933), p 77; Christopher Marshall, The Diary of Christopher Marshall (Amazon Digital Services, 2014) p 69; Bruce Bliven, Under the Guns, New York 1775-1776 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972) p 279; Pennsylvania Journal, April 10, 1777; Maryland Journal, May 1, 1776; Library of Congress, NY Gaz & Weekly Mercury, reel 2904; New York Gazette & Weekly Mercury, May 27, 1776; Pennsylvania Journal, April 17, 1776; Virginia Gazette [Dixon and Hunter; Williamsburg], 22 June 1776; Pennsylvania Ledger, vol. 1, Jan. 1775-Nov. 1776; Pennsylvania Evening Post, June 13, 1776; Letters of Delegates to Congress: Volume 4 May 16, 1776 - August 15, 1776; http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/D?hlaw:3:./temp/~ammem_s9BZ:: Paul Burgess, A Colonial Scrapbook; the Southern New Jersey Coast, 1675-1783 (New York, Carlton Press, 1971) pp 107-8; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 1, pp. 110, 117.