The "Tory Ascendancy" in Shrewsbury and Down the Shore

by Michael Adelberg

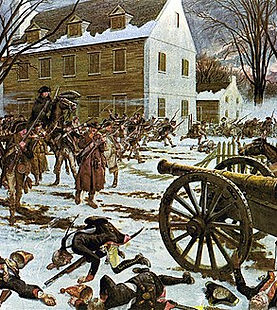

At the Battle of Trenton, the Continental Army routed the Hessians and turned the British Army back toward New York. Monmouth County volunteers joined the Continental Army for the attack.

- December 1776 -

As discussed in other articles, in late November, 1776, the Continental Army retreated across New Jersey and the British Army entered New Jersey. On November 30, General William Howe, the British Commander in Chief, invited the citizens of New Jersey to sign a loyalty oath and receive British protection from any future rebel harassment.

Across New Jersey, but particularly in Monmouth County, disaffected New Jerseyans switched sides. In Monmouth County, Loyalist insurrections sprung up in Upper Freehold, Freehold-Middletown, and from Shrewsbury down the shore. The December 1776 Loyalist insurrection that occurred from Shrewsbury to Toms River was less organized than the insurrections in Freehold-Middletown and Upper Freehold. This may have been more a reflection of the region’s far flung geography than a lack of disaffected residents to power the counter-revolt.

Just a few weeks before the December insurrection, Samuel Wright’s Loyalist association from the neighborhoods of Long Branch, Deal and Shark River was exposed and broken up. Wright and twelve of his men were captured. Immediately after, Colonel Charles Read of Burlington County led a short campaign that captured 70 more Loyalists. These events removed more than 80 committed Loyalists just before the start of the general insurrection. But even with these men in prison, there were many disaffected residents in the shore communities ready to support the British.

The Insurrection Begins

Pro-British rioting occurred immediately after Charles Read’s militia left Shrewsbury Township. On December 1, John Halloway, a Shrewsbury Township yeoman, plundered the home of Garrett Longstreet, an officeholder under the new government. According to the Supreme Court Indictment, Halloway led a gang of ten men who:

With force and arms, to wit, sticks, staves, swords, guns and other offensive weapons… assembled and gathered together at the dwelling house of Garrett Longstreet, there situated, unlawfully & riotously did break open & enter a quantity of rum, sugar and cyder belonging to certain persons... in the said dwelling house, did take and carry away.

This riot occurred on the eve of the insurrection—an insurrection that would begin with the return of John Morris and his battalion of Loyalists.

The prior July, Morris (a former British Army officer who settled near Manasquan in the 1760s) led 68 Shrewsbury Loyalists to Sandy Hook and joined the British Army. They became the 2nd Battalion of the New Jersey Volunteers. When the tide of the war shifted and the British Army marched into New Jersey, Morris’s Loyalists entered Shrewsbury, probably on December 3. On that day, Robert Bowne, a Shrewsbury merchant, wrote that the British were “9 or 10 miles this side of Amboy, which has occasioned the Provincials [Morris’s men] to brave the guards along the coast."

Bowne also noted that his kinsman, Thomas Bowne, from Queens, New York, was illegally traveling back and forth and transporting goods between Shrewsbury and British-held New York:

Thomas has been down here several times this fall... the last he was here was about two weeks ago, when he brought down 1500 [Continental] dollars. Seeing no prospect of laying it out to advantage in these parts, we concluded [it] best for him to go to Virginia and lay out the same.

From this letter, it can be inferred that disaffected Shrewsbury farmers were consorting with pro-British New York traders and that Continental dollars were not viewed as valid tender along the largely disaffected shoreline. Corroborating evidence of this is provided in prior articles about New York Loyalists hiding out in Shrewsbury and disaffected residents refusing to muster for the Monmouth militia.

Loyalists Take Control

A number of militiamen, including William Brinley of Shrewsbury, “laid down their arms” on the arrival of John Morris’s armed Loyalists. This may have forced several Shrewsbury Whigs (supporters of the Revolution) to leave the township in early December. William Davis, a solid Whig from Shrewsbury Township, recalled that he “volunteered under Benjamin Dennis to go to Philadelphia to join General Washington.” But his party of Shrewsbury volunteers did not make it.

On the way to Philadelphia, prior to reaching Freehold, Davis “with some others (among whom was Captain John Dillon of Dover) were captured by a scouting party of British Colonel John Morris - He was then marched direct to the City of New York. There he was detained as a prisoner for 22 months.” It is impossible to know whether Davis’s decision to leave Shrewsbury was motivated by patriotism or the need to avoid arrest back home.

Other Shrewsbury Whigs did make it to the Continental Army. Thomas Patten, for example, left Shrewsbury for the Continental Army:

I entered a company of volunteers who were forming for the purpose of operating with the Army of Washington against the Hessians at Trenton... I was severely wounded by a musket ball near the Assunpink Creek & being removed to Pennington, New Jersey was confined there.

One of the first of Morris’s Loyalists to return to Shrewsbury was Thomas Okerson, formerly of Tinton Falls (and a lieutenant in the New Jersey Volunteers). He was sent back into Shrewsbury township to capture an unnamed militia officer (probably Colonel Daniel Hendrickson or Lt. Colonel Aucke Wikoff, both of Tinton Falls). But Okerson was ordered to show restraint when making the capture, "you are on no account to touch his life.” There is no record of Okerson making the capture. An aversion to violence characterized the Shrewsbury insurrection—this aversion would not last the war.

John Wardell, the former judge whose disaffection was exposed by David Forman weeks earlier, was appointed Commissioner for administering British oaths in Shrewsbury. His name appeared as one of three commissioners (along with John Taylor and John Lawrence) on an advertisement circulated across the county calling on citizens to “qualify” for British protection. As Wardell began administering oaths, John Morris pushed south toward Toms River in Dover Township.

Captain Robert Morris (not related to John Morris) remained in Shrewsbury with a newly-raised company of New Jersey Volunteers. James Corneilius would later testify that Morris was assisted by two disaffected Quakers, Walter Curtis and Peter Brewer:

Sometime about the latter end of December last, saw the above Walter Curtis with the enemy & in company with Robert Morris at the town of Shrewsbury, and at the same time that he saw Peter Brewer with sd Morris and his party.

John Morris reached Toms River on December 23. Another article discusses his meeting with Thomas Savadge, the Administrator of the Pennsylvania Salt Works, the largest enterprise in the township. Morris chose to spare the salt works and left them in the custody of two local Loyalists. Morris apparently relied on Joseph Salter (the first militia colonel for the area, but now disaffected) to line up residents to take British loyalty oaths. Salter induced many to sign. Daniel Griggs of Toms River later recalled Salter’s approach:

About the 27th day of December last, he, sd deponent, did sign a paper of protection of Col John Morris at Toms River, of which sd paper Joseph Salter, of the township of Dover, was the first signer. The sd Mr. Salter was very often at the deponent's house in company with sd Morris & his officers, that on a certain day the sd Salter clapt his hand on the deponent's shoulder & said 'the times are very much altered, as [I] always expected it would be'.

Thomas Potter, of Toms River, vividly recalled John Morris’s visit to Toms River and the prominent role played by Joseph Salter in supporting the Loyalists. In an April 1777 deposition, Potter described "being sent for by Colonel Morris & threatened to be sent to the guard house if he did not come.” Potter went to the house of John Cook, the senior militia officer at Toms River, “where he saw Joseph Salter of said county & John Williams with the said colonel John Morris.” Morris showed Potter “a paper with a number of signers & that the first name subscribed thereto was Joseph Salter.” He was told that the “purpose of the said paper was to put us on the same footing we formerly were, under the King.”

Potter was compelled to sign and accept British protection when Major John Antill of Morris’s battalion “tendered him an oath of allegiance to the King.” When Potter initially declined, “Morris told him that unless he [Potter] did [take the oath], he [Morris] would strip him of everything, upon which & being also threatened to be sent to the guard house & the said oath being explained to him [Potter] by the said Salter, he at length complied.” Because Potter had accepted British protection, he was told by Salter that he did not need to surrender his gun.

The End of the Insurrection

But time was running out on the nascent Loyalist association that Potter had just joined. On January 2, 200 newly-mustered Loyalist militia from Upper Freehold, Freehold and Middletown townships were routed in a short battle near Freehold. The British Army, defeated at Trenton and Princeton, pulled back across New Jersey. John Morris took his troops out of Monmouth County and the most strident Loyalists either joined him or went into hiding.

The first Pine Robber gangs, covert Loyalists operating in salt marshes along the shore, included Loyalists who fled as the Loyalist insurrections crumbled. Concealing Loyalists was dangerous. Richard Lippincott, a disaffected Shrewsbury resident who had received a loan to start a salt works the prior summer, was accused of aiding a Loyalist-in-hiding; for this, he was jailed in Burlington County. On release, Lippincott fled to British-held New York. By the end of war, he would be the most despised man in Monmouth County for hanging Joshua Huddy.

Related Historic Site: Washington Crossing Historic Park

Sources: New Jersey State Archives, Supreme Court Records, State v John Halloway, # 35895; New Jersey State Archives, Supreme Court Records, State vs Samuel Longstreet, #36663 and 36665; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - William Brinley; New Jersey State Archives, Bureau of Archives of History, Council of Safety, James Cornelius; Robert Bowne to Thomas Bowne, Rutgers University Special Collections, AC 1246; New Jersey State Archives, Bureau of Archives of History, Council of Safety, box 1, document #3; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, William Davis of Ohio, www.fold3.com/image/#14680717; National Archives, Revolutionary War Veterans' Pension Application, Thomas Patten of NJ, www.fold3.com/image/#27227091; Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution, 2 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1864), vol. 2, p 562. Jones, E. Alfred. The Loyalists of New Jersey, (Newark, N. J. Historical Society, 1927) p 165; Deposition of Daniel Griggs, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 4, April 7, 1777; United Empire Loyalists, Loyal Directory, Richard Lippincott: http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info. United Empire Loyalists, Loyal Directory, Richard Lippincott: http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info; Deposition of Thomas Potter, New Jersey State Archives, William Livingston Papers, reel 4, April 7, 1777.