David Forman's Drift into Martial Law and Scandal

by Michael Adelberg

As he led the New Jersey Militia in the defense of the Delaware River, the New Jersey Assembly held hearings into David Forman’s conduct. This pushed Forman to resign as a Brigadier General in the militia.

- March 1777 -

In March 1777, David Forman was the colonel of an “Additional Regiment” of the Continental Army stationed in Monmouth County and one of four Brigadier Generals of the New Jersey Militia (commanding the Monmouth County militia and the militias from Burlington and Middlesex counties). In his first military campaign as the most powerful man in Monmouth County, Forman led 250 men in a doomed attempt to dislodge the British from Sandy Hook. He narrowly averted disaster by retreating quickly off Sandy Hook before a British ship could land men behind him and trap him on the narrow peninsula.

Throughout the Revolution, Forman often took actions that stretched the boundaries of the law. On February 27, 1777, he wrote Captain John Covenhoven (not the legislator of the same name): "You are hereby directed immediately to turn out all the men of your district capable of bearing arms… and march them to join me." On March 3, Forman issued a certificate to Obadiah Holmes: "Mr. Obadiah Holmes is hereby exempted from militia service, I have been satisfied and informed by his physician of his nervous system will not admit his doing camp duty." At the time, Forman was a Continental Army officer without authority to direct militia; he exceeded his authority both times. That authority would soon be granted, however.

Forman’s Orders and Commissions

On March 5, Forman was commissioned the Brigadier General over the Monmouth Militia. A letter from Governor William Livingston noted that Forman was given power to call out the neighboring county militias so the New Jersey Legislature would not have to give the unpopular order themselves. The governor wrote, "it was easier to invest him [Forman] with the power of calling out the militia of Monmouth, Middlesex and Burlington, without giving umbrage to some of the Colonels of those regiments." But Livingston also noted that the Burlington County militia is "exceedingly dilatory in their motions" and the Middlesex militia "will probably be of as much service at home as they can be elsewhere."

After his unsuccessful attack on Sandy Hook, Forman turned his attention to improving the performance of the Monmouth militia by rooting out the county’s disaffected. Several weeks were spent preparing for a general muster of the three Monmouth militia regiments and forcing each militiaman to take a loyalty oath to the New Jersey and Continental governments on May 1. The plan was controversial and prompted a flurry of letters between leaders including George Washington and Governor Livingston. This general muster is the subject of another article.

Forman was rightly concerned that disaffected residents on the shore were illegally trading with the British and that provisions formerly belonging to Loyalist refugees were vulnerable to capture by Loyalist parties. He wrote General Washington and Governor Livingston about the concern. Livingston wrote:

Col. Forman further informs me that many of the people who have absconded have left behind them stocks of horses, cattle and grain, which will not only be lost to the owners, but to the public... The Colonel will take possession of such effects for public use.

Livingston concurred, "I think the removal of provision in the County of Monmouth within reach of the enemy of such consequence that I shall direct Colonel Forman to set about that work."

On April 21, Washington concurred and gave Forman authority to impress provisions, "I have transmitted copies of the resolve upon this subject to Genl. Putnam [Israel Putnam] and Colonel Forman (the latter of whom is in Monmouth County) with orders to execute them." Because the order no longer exists, it is impossible to know the breadth of Forman’s power to move against individual citizens without due process under New Jersey law.

Forman Stretches His Authority into Civil Law Enforcement

Forman, with these orders, put himself into affairs that would normally fall to civil government. He arrested and sent John Taylor to Haddonfield to appear before the New Jersey Council of Safety. Nathaniel Scudder of Freehold was on the Council and received a letter from Forman. Forman stated that Taylor confessed "that he had freely taken oaths of allegiance to the King & always should himself be bound by that oath." Taylor was not in arms or in active revolt when he was sent forward. So, it is unclear why Forman, as a military commander, was concerning himself with Taylor rather than letting the county sheriff and township magistrate consider Taylor’s past actions.

Forman also took an interest in John Taylor’s brother, Edward Taylor. Edward had been a committeeman and a delegate to the New Jersey Provincial Congress. But he became disaffected after the Declaration of Independence and was the only member of the Middletown Baptist congregation to vote against excommunicating its Loyalist members (including John Taylor). Most irksome to Forman, Edward Taylor was the father of George Taylor, who led several raids into Monmouth County in June 1777 and skirmished with Forman.

On July 2, Forman moved against Edward Taylor for “acting as a spy amongst us” and “giving aid to a party of Tories and British, commanded by your son.”

I do therefore enjoin you for the future to confine yourself to your farm at Middletown, and do not attempt to travel the road more than crossing it to go to your land on the north side of said town... under risk of being treated as a spy.

In punishing Edward Taylor, Forman was, in effect, acting as a one-man legal system based primarily on family ties.

Forman also took action against the Shrewsbury merchant, Thomas Dowdeswell. According to Dowdeswell’s post-war Loyalist compensation claim, in 1777, his Loyalist views "caused me to be attacked and plundered of my goods and property on two different times, to the amount of £100 and upwards, by a company under the command of Genl. Forman in Monmouth County.” He further wrote, “I was confined in the town of Monmouth about 5 days under a guard; after which I was obliged to put myself under the protection of General Clinton at New York."

Greater Controversies in Fall 1777

Forman’s drift toward his version of martial law continued as the year went on. He assigned his Continental regiment to the Union Salt Works—a large salt work on the Manasquan River in which he owned a controlling interest. And Forman reportedly used those troops as a labor force at his salt works and harvested wood from the private land of Trevor Newland, a former British Army officer living on the shore and owner of a competing salt work. This controversy is the focus of another article.

Then, in September 1777, Forman captured Stephen Edwards, a Loyalist refugee taken at the house of his family. Edwards was subjected to a military tribunal that Forman convened and hanged on Forman’s order. Forman lacked authority to take this action. The New Jersey Council of Safety existed to try and punish Loyalists and Forman had sent other Loyalists to the Council. The hanging of Edwards inflamed Loyalist resentments and provoked later violent retaliatory acts.

In September, Forman exiled Loyalist women from Monmouth County without apparent authority to do so (a June 1777 law empowered him to allow people to go to New York, but not force them). Robert Lawrence, an elder squire, was the father of Mary Leonard, the wife of a Loyalist officer in the New Jersey Volunteers and one of the exiles. Lawrence protested to the New Jersey legislature: “David Forman presumed to banish some women out of this State into enemy lines, whereupon I apprehended that our new & happy constitution had received a very dangerous wound.” Lawrence concluded that Forman’s behavior was like that of “some African tyrant." Forman’s moves against Mary Leonard are discussed in another article.

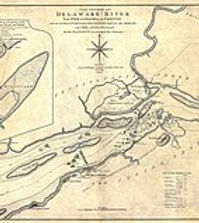

Yet Forman also distinguished himself in driving the Monmouth County militia to the Sourland Hills and joining the Continental Army as the British Army went into motion in June 1777. And in September he raised militia and his regiment to march across New Jersey to fight with the Continental Army at the Battle of Germantown. After that, Forman went home to Freehold, raised more men, and returned on October 26th to participate in the defense of Red Bank (on the Delaware River) as the British laid siege. Forman also provided valuable, if uneven, intelligence reports on British movements through observations of British movements at Sandy Hook, interrogations of people coming into Monmouth County, and maintaining informants in New York.

At this time, Forman became embroiled in a dispute with General Silas Newcomb, also a Brigadier General in the militia. Red Bank was in Newcomb’s home county of Gloucester. Both generals sent letters to Governor Livington complaining about the other. General Washington intervened in Forman’s favor, writing to Livingston “If you would only direct him [Newcomb] to obey General Forman as a senior officer, much good to the service would result from it.” Livingston then wrote Newcomb:

I am extremely sorry to find that there should be any difference between you and General Forman at so critical a season... He [Forman] undoubtedly has a right to command you without any such derivate authority. You will therefore entertain no thoughts of dismissing the men you have assembled, but furnish General Forman with a return of them & resign command of them to him.

Meanwhile, the New Jersey Legislature was receiving petitions from Monmouth County complaining of Forman’s conduct while home in Freehold for the annual county election on October 14. One of those petitions has survived:

General Forman, assisted by Lt Col [Thomas] Henderson, harangued the people on the conduct of the late Assemblymen & candidates for the present Assembly... and threatening to cram the votes down the throat of one of the late members, then a candidate for the present one and confine him with his guards, and many other threats.

Forman’s conduct at the 1777 election is the subject of another article.

With the list of controversies building, the New Jersey Legislature chose to investigate Forman. Forman turned down a summons to appear before the Legislature on November 5 because “of the necessity he was under of being absent under important military command at the time the hearing was appointed.” He requested that the hearing be postponed. The Assembly decided to hold the hearing, but ruled that Forman need not attend. The next day, the Assembly re-read Lawrence's memorial.

On November 9, Forman resigned his General's commission in the New Jersey militia. By doing so, Forman deprived the New Jersey Legislature of a lever to punish him because he no longer held a state office. (He retained his Colonel's commission in the Continental Army.) Governor Livingston wrote General Washington about the affair, "General Forman has, to my great concern, and contrary to my warmest solicitations, resigned his commission upon some misunderstanding with the Assembly."

On November 11, the Legislature heard from several Monmouth petitioners and the county’s election judges about Forman’s conduct at the county election. Petitions were re-read. The next day the Assembly voted 13-12 to void the Monmouth election – despite all three Monmouth delegates voting against. It ordered a new election.

The Loyalist New York Gazette half-correctly reported Forman’s resignation on November 23:

We are informed that General David Forman has been removed of his command as a General in the Rebel Army, in consequence, it is said, of a memorial preferred against him by the inhabitants of Monmouth County, New Jersey, which expressed their abhorrence for the monstrous and deliberate murder of Stephen Edwards of Shrewsbury.

The New Jersey Legislature was not done with Forman. It asked Geroge Washington to remove Forman’s Additional Regiment from his command—a move Washington reluctantly agreed to in January 1778. This is the subject of a different article.

David Forman was a man of boundless energy who many times exerted himself for the Revolution and exposed himself to danger. Forman was robbed in December 1776 and was the target of a Loyalist raid in spring 1777. George Washington and William Livingston recognized his zeal and supported him. Yet, Forman wielded power recklessly—sometimes for petty revenge and sometimes to further his financial interests. The majority of Forman’s peers in Monmouth County leadership, the men who knew him best, supported moves to check his power. The actions of the Legislature in 1777 did not end Forman’s controversial public service. He would re-emerge later in the war as the head of vigilante organization and he would instigate a new set of scandals.

Related Historic Site: Red Bank Battlefield

Sources; David Forman to Capt. John Covenhoven, National Archives, Misc. Numbered Records, 4020; William Horner, This Old Monmouth of Ours (Freehold: Moreau Brothers, 1932) p 213-6; Archives of the State of New Jersey, Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey (Paterson, NJ: Call Printing, 1903) vol. 1, p 321; George Washington to William Livingston; William Livingston to George Washington, John Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1932) vol. 7, pp. 344, 363; William Livingston to George Washington, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 1, p 292-3; Deposition, David Forman, New Jersey State Archives, Bureau of Archives of History, Council of Safety, box 1, document #17; Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), p202-3; The Grover Taylor House, (Monmouth County Historical Association: Freehold, New Jersey) p 22-4; Thomas Dowdeswell, Rutgers University Library Special Collections, Loyalist Claims Applications, AO 13/96/235; The Library Company, New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, October 3, 1777, p 193 and November 4-12, 1777, p 5-17; Library of Congress, Rivington's New York Gazette, reel 2906; Robert Lawrence, petition, New Jersey State Archives, Bureau of Archives and History, Manuscript Coll., State Library Manuscript Coll., #129; David Forman, Certificate, March 3, 1777, Monmouth County Historical Association, Cherry Hall Papers, box 6, folder 5; George Washington to William Livingston, John Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1932) vol. 7, pp. 344, 363; George Washington to Congress, Official Letters to the Honorable Congress (London: Caddel, Junior & Davies, 1795) vol 2, p61; Robert Lawrence to New Jersey Legislature, New Jersey State Archives, Bureau of Archives and History, Manuscript Coll., State Library Manuscript Coll., #129; Petition, unsigned, Monmouth County Historical Association, Cherry Hall Papers, Photocopy; Minutes on the Monmouth Election in New Jersey Votes of the Assembly, November 4-12, 1777, The Library Company, p 5-17; George Washington to David Forman, Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4, reel 45, October 25 - 31, 1777; George Washington to William Livingston in John Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1932) vol. 9, pp. 485-6. Library of Congress, Papers of the Continental Congress, reel 168, item 152, vol. 5, p 161; William Livingston to Silas Newcomb, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 2, pp. 99-100; William Livingston to George Washington, Carl Prince, Papers of William Livingston (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1987) vol. 2, p 108.