British Army Marches Through Middletown to Navesink Highlands

by Michael Adelberg

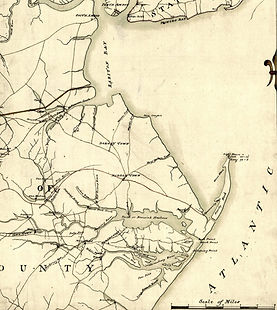

This British Army map of northeast Monmouth County shows Middletown as the midpoint between hostile inland villages like Colts Neck (called “Jewstown”) and safety at Sandy Hook.

- June 1778 -

As discussed in prior articles, following the Battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778), the British Army marched east through Middletown on its way to Sandy Hook. It would take the British Army a week to travel only 25 miles. Despite wanting to leave New Jersey, the British commander, General Henry Clinton moved his troops slowly from Middletown. He wrote of waiting there two days "in hopes that Mr. Washington [George Washington] might have tempted to advance to a position near Middletown." Dr. John Campbell of the British Army was more explicit:

The army marched without farther opposition, where they waited two days, in hopes that General Washington might be induced to take post near Middletown, where he might have been attacked to [our] advantage.

Washington, however, had consulted with Monmouth County leaders, and understanding the inferior ground he would possess, chose not to pursue the British. He sent only a small force led by Colonel Daniel Morgan, accompanied by Monmouth militia, to shadow the British.

The British baggage train, with a sizable guard, left Freehold for Middletown even before the Battle of Monmouth began. It was attacked twice on June 28, but the heat was the greater enemy that day. A German Quartermaster officer wrote, "The heat was so enormous today that almost the whole regiment was sick… Many men fainted during the day and some died on the spot." The baggage train stopped at Nut Swamp that evening, three miles from Middletown.

The main body of the British Army, after fighting the Battle of Monmouth, rested until midnight and then left Freehold for Middletown. A German Officer Heinrich von Feilitsch wrote, "Our column marched all night… at five o'clock in the morning we halted three miles from Middletown." The British Army entered Middletown in the morning of June 29. John Peebles, a British Officer, described Middletown: "This little village surrounded with hills is about 2 or three miles from Raritan Bay, and about 12 miles from the Light House."

The British Camp at Middletown

General Clinton established his headquarters at the house of John Taylor, the town’s largest home. Taylor had led a Loyalist insurrection in the township in 1776. The British took most of Taylor’s livestock while in Middletown, but compensated him for the taken animals. According to militiaman Albert Vanderveer, Clinton also “issued a proclamation offering protection to all inhabitants who would not take up arms against them.” At least one family took the opportunity to leave with the British. Israel Bedell’s family left Middletown with the British and settled on Staten Island afterward.

The British stay in Middletown did not include the arsons that marred its stay at Freehold. However, there were several incidents. John Truax, a militiaman, recalled that on June 30 "he was robbed when the Army passed through the Country." John Tilton recalled that his family’s Bible was "destroyed by the British in their retreat through Middletown in June 1778." For many middling farm families, the family Bible was the only book they owned and many families recorded births and deaths in it. So, the destruction of the family Bible was an act of cruelty.

Antiquarian sources also discuss the looting of two Middletown homes by German soldiers. General William Knyphausen commandeered the homes of Richard Crawford and James Paterson for his senior officers. Both homes were looted of their silver. Women camp followers further reportedly plundered Mrs. Crawford of all her clothes. When the Germans left Middletown, a party of stragglers remained behind at Crawford's and was reportedly surprised by a party of mounted Continentals. The Americans recovered some of the lost goods and killed a local Loyalist guide named Hankinson. Knyphausen also reportedly took Paterson’s seven horses and forced him to accompany the Germans as a guide for two days, before releasing him with one of his horses. Paterson's amiable release led to his arrest for treason (he was found not guilty). The Germans also reportedly burned a barn known as “the Old Fort” because it was a militia meeting place.

Middletown’s Baptist congregation, which had purged its Loyalist members a year earlier, was also targeted. Minister Abel Morgan held Sunday service on June 28 with cannon fire from the Battle of Monmouth audible in the distance. However, on July 5, he recorded: “There was no meeting on this Lord's day because of the enemy's passing thro' our town the week past, putting all in confusion by their plundering and ravaging as they went." Morgan wrote again on July 10 about holding a meeting “in mine own barn, because the enemy had took all the seats in the meeting house in town.” He did not preach again until July 19—and then he preached in a barn "because the enemy had took all the seats in the meeting house." Morgan did not preach again in the meeting house until August 30.

Three Loyalist officers were court martialed for actions taken after the Battle of Monmouth. Lt. Boswell of the Maryland Loyalists was tried for horse theft. He reportedly “took two horses, property of the inhabitants of the Jerseys… contrary to the General order issued by General Sir Henry Clinton against plundering and marauding." Captain Martin McEvoy of the Roman Catholic Volunteers "behaved in an ungentlemanlike manner, plundering in the Jerseys in taking a horse and a cow, and behaving indecently in parade"—or at least he was accused as such. Captain John McKinnon, also of the Roman Catholic Volunteers, was tried for ungentlemanlike behavior, including "plundering in the Jerseys." McKinnon was found guilty and cashiered from service.

A few additional incidents occurred as British forces moved east from Middletown. According to an antiquarian source, Rebecca Dennis, the wife of militia Captain Benjamin Dennis, was struck by a German soldier with his gunstock. Noah Clayton of the Shrewsbury militia recalled being captured by British regulars: “I went to S'berrytown and [was] taken prisoner by the 42nd Regiment of Highlanders, from thence I was taken to New York, where I remained for better than two years."

The hot weather that harried the British during the march across New Jersey continued. German officer, Charles Von Krafft, wrote of his camp at “Mittletown” on June 30. The soldiers camped on “a large hill” to lessen the heat, but to little effect. “Huts were built, but owing to the heat, it was almost impossible to breath underneath them."

An antiquarian source suggests June 30 was the start of the infamous Pine Robber career of Lewis Fenton (he deserted from the Loyalist New Jersey Volunteers just a few days earlier). Fenton reportedly went to the farm of the Cooper family two miles south of Freehold and demanded food from Mrs. Cooper and her two daughters. However, before Fenton could carry away the food, he was chased off by five German deserters who unwittingly came onto the scene. The Germans took the food and Fenton went into hiding. He assembled a small band in Tinker Swamp near Manasquan that soon robbed widow Harris and her tavern—starting his outlaw career.

British Army Moves toward Sandy Hook

Irrespective of the disorders, the British continued to occupy Middletown and parts of the army spread east to the Navesink Highlands. A German officer, Jacob Piel recorded that on June 30 "camped in the woods near the Shrewsbury River" and then the Navesink Highlands on July 1. Near there, a meeting occurred between General Clinton and officers of the Royal Navy.

Captain Henry Duncan of the Royal Navy wrote of the July 1 meeting: "Anchored outside Sandy Hook, Sir H. Clinton arrived near there and sent off an express requesting to see me as soon as possible… we met Sir Henry at the Neversink." According to Colonel Thomas O’Bierne, who attended the meeting, the officers discussed the arrival of the French fleet off Cape May. As a result, "the utmost expedition was now requisite to take off the troops, that… they might be placed in safety [in New York]." Clinton would no longer dither at Middletown hoping to tempt Washington into attacking.

Clinton now moved the entire army toward Sandy Hook. General James Pattison wrote that "we gained the heights of the Neversink" on the evening of July 1. According to antiquarian sources, Henry Clinton used the houses of James Stillwell and Richard Hartshorne as his temporary headquarters while camped on the Highlands. Hartshorne’s house may have been the headquarters of the Monmouth militia a year and a half earlier when it was routed by British regulars at the Battle of the Navesink.

The British did not feel threatened by Colonel Daniel Morgan’s regiment and the Monmouth militia that shadowed them. German Capt. [?] Hiendrich wrote that the camp was “naturally secure.” Von Feilitsch, at Middletown on July 1, wrote that "the enemy patrol approached but did not make contact." British Army Officer, Andrew Bell, wrote on July 1 that there was "no firing of any consequence since the action on Sunday." On July 2, O’Beirne wrote: "the enemy did not dare pass the heights of Middletown" and that the British now camped on the Navesink "without molestation." That same day, Captain Hiendrich wrote that his men “lay completely quiet” at Middletown.

However, two other British Army officers noted skirmishing at Middletown as the British began to withdraw. On July 1, Peebles wrote that the enemy was “expected” and that skirmishers “are still hovering about us, showing themselves in different places in our front & right, [taking] some popping shots." Johann Ewald, a German officer recalled being in a more considerable engagement at Middletown on July 1:

Today a strong enemy corps appeared here from Middletown. A sharp engagement between the Jaegers and the enemy riflemen, in which three Jaegers were killed and five wounded. Toward evening, the enemy withdrew.

Skirmishing, it appears, is in the eye of the beholder. For those not engaged, it was easy to dismiss skirmishing as minor. But when directly engaged, skirmishing could be a “sharp engagement.” Ewald further reported a second engagement on July 2, "although the patrol was cautious, it was attacked unexpectedly by the enemy, and one Jaeger was killed and two captured."

By July 3, Henry Clinton had moved the entire army to the Navesink Highlands and the British began moving their baggage onto Sandy Hook—the move would be completed with considerable help from the navy on July 5. The Monmouth Campaign had caused the British Army considerable losses—300 battlefield dead, several hundred desertions, and several dozen more deaths along the line of march from heat and skirmishing. After nearly three weeks of marching, fighting, and enduring many hassles and privations, the soldiers were truly safe again.

Related Historic Site: Historic Portland Place

Sources: Henry Clinton’s letter printed in New York Journal as printed in Frank Moore, Diary of the American Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner, 1865) v2, p68-9; Abel Morgan’s sermons in Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), pp. 522-3; Stephen Jarvis, An American's Experience in the British Army, Journal of American History, v1, n3, 1907, p452. New York Historical Society, MSS Microfilms, reel 17, Stephen Jarvis Autobiography, p 30; John Campbell, Biographica Nautica, Memoirs of an Illustrious Seaman () p 482; William Stryker, The Battle of Monmouth (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1927) p 232; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Truax; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - John Tilton; John Stillwell, Historical and Genealogical Miscellany (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1970) v5, 50-9; Correspondence from Don N. Hagist, British Court Martials; Great Britain, Public Record Office, War Office, Class 71, Volume 87, pages 179-181; Samuel Smith, The Hessian View of America, (Monmouth Beach, N.J.: Philip Freneau Press, 1975) p 20; Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), p199; John U. Rees, "What is this you have been about to day?" The New Jersey Brigade at the Battle of Monmouth, 2003, Appendix I link: https://revwar75.com/library/rees/monmouth/MonmouthA.htm; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Noah Clayton; John C. Paterson, The Pine Robbers of Monmouth County, unpublished manuscript in the collection of the Monmouth County Historical Association, 1834, p 1-2; Peter W. Coldham, comp., American Loyalist Claims (Washington, D.C.: National Genealogical Society, 1980), p 534; Journal of Daniel Youngs, Brooklyn Historical Society, New York State-New York City, 1778-1788, coll. 1974.002; Abel Morgan’s sermons in Franklin Ellis, The History of Monmouth County (R.T. Peck: Philadelphia, 1885), pp. 522-3; Henry Clinton to Richard Howe, Clements Library, U Michigan, Henry Clinton Papers, 6/29/78 & 7/1/78 & 7/3/78; David Library of the American Revolution, James Pattison Papers, reel 1; Mary Hyde, Retreat after the Battle of Monmouth, Spirit of '76, vol. 5, 1899, p253; John Parke’s Account in Pennsylvania Archives, Pennsylvania Historic & Museum Commission, reel 14, frame 0338; Stephen Moylan to George Washington, Library of Congress, George Washington Papers, Series 4, reel 50, June 29, 1778; John Peebles, John Peebles' American War, p221-8; John Knox Laughton, "Journal of Capt. Henry Duncan" in Publications of the Naval Records Society, vol. 20, 1920, p169-70; Thomas Lewis O'Beirne, A Candid and Impartial Narrative of the Transactions of the Fleet, Under the Command of Lord Howe (London, 1969), pp. 8-9; Francis Downman, The Services of Lieut. Colonel Francis Downman (London: Royal Artillery Institution, 1898) p64-72; Bell, Andrew, "Copy of a journal by Andrew Bell, Esq., at One Time the Confidential Secretary of General Sir Henry Clinton. Kept during the March of the British Army through New-jersey in 1778.” Proceedings of the New jersey Historical Society, vol 6, 1851, p18; Bruce Burgoyne, Journal of the Hesse Cassel Jaeger Corps (New York: Heritage Books, 1987) p43-7; National Archives, revolutionary War veterans Pension Applications, New Jersey - Albert Vanderveer; Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979) pp. 136-7; Mary Hyde, Retreat after the Battle of Monmouth, Spirit of '76, vol. 5, 1899, p254-5Bruce Burgoyne, Diaries of Two Ansbach Jaegers (NY: Heritage Books, 1997) p42-3; Jared Sparks, Correspondence of the American Revolution: Being Letters of Eminent Men (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1853) pp. 152-3; Jones, E. Alfred. The Loyalists of New Jersey, (Newark, N. J. Historical Society, 1927) p 261.